Introduction

Introduction

From December 17 to 25, 2006, at Sravasti Abbey, Geshe Jampa Tegchok taught on A Precious Garland of Advice to a King by Nagarjuna. Venerable Thubten Chodron complemented these teachings by giving commentary and background.

- Background of the teachings

- Nagarjuna’s short biography

- Buddhist worldview of cyclic existence, karma, bodhicitta

- What it means to be a person

- Questions and answers

Precious Garland 01 (download)

We’re going to embark on this adventure of listening to the teachings of the Precious Garland with Khensur Rinpoche. So I wanted to give an introductory talk setting the stage, the background for the worldview he’s going to be speaking in. But before doing that I thought that we would do some of the prayers, our little choir practice, and also do them as a way for preparing our own minds for the teachings, not just learning how to chant. And have a little bit of silent meditation and then I’ll give the talk.

[Chanting follows with silent meditation]

Motivation

Before we begin let’s spend a moment cultivating our motivation. So it’s good to ask ourselves, “What was our initial motivation for coming here?” So just reflect on that a little bit. What kinds of thoughts and attitudes brought us to be here in this room today embarking upon the teachings of the Precious Garland?

[More silence]

And whatever our initial motivation was, let’s amplify it and expand it. And remembering that our life has come about and is completely dependent upon the kindness of sentient beings, let’s cultivate an attitude of gratitude and appreciation for other sentient beings. If we train our mind in gratitude in that way, then the judgment falls away and we can see others as lovable because their kindness to us remains very prominent in our mind. And then, reflecting on our own misery in cyclic existence of birth, ageing, sickness, death and everything that happens in between; see that that’s also the situation of all other sentient beings. And just as we want to be free and have lasting happiness, so do they. And so, in order to bring about their happiness, we have to free ourselves from all of our own internal hindrances and obscurations, and develop our own potential and capacity completely. And so it’s for this reason that with a compassionate motivation we generate the aspiration for full enlightenment in order to benefit all living beings. And so generate that aspiration.

Khensur Jampa Tegchok Rinpoche’s life

I thought before giving you the world view that Khensur Rinpoche is going to speak from, I’d talk a little about his life and Nagarjuna’s life.

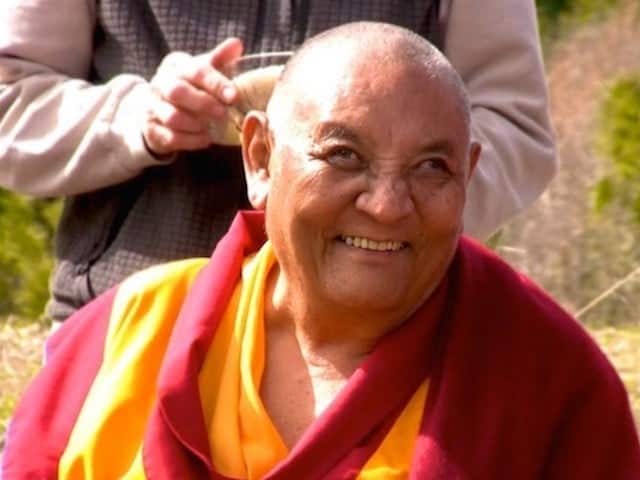

Khensur Rinpoche was born around 1930, so he’s 76 now. He was born in the Pempo region of Tibet which is outside of Lhasa. And the Pempo, that’s actually where Lama Tsongkapa wrote the Lamrim Chenmo, in that area of Tibet. And I’m not sure how old he was when he went to Sera, but he trained in Sera Monastery, which is one of the three great large monasteries in Lhasa. And he trained there for a number of years until 1959 when there was the abortive uprising against the Chinese Communist occupation. And then he wound up fleeing to India as a refugee. And my guess is, I’m pretty sure he was at Buxa—which was the old British POW camp that they used during World War II—which became the refugee camp for the Tibetans in ’59 and ’60. And then at some point he went down to south India. The Indian government was incredibly kind. India, in spite of being so poor, provided asylum for tens of thousands, and now hundreds of thousands of Tibetans and gave them land in various parts to erect their settlements. So Sera was given some land in south India outside of Mysore and the land had, as I heard it, lions and tigers and I don’t know about bears, but Ho Ho! And so the monks had to clear the land and build their monasteries from the very beginning.

And then it must have been in the late 70’s after Manjushri Institute was founded by Lama Yeshe as one of the early centers of the FPMT. Then because Lama was also from Sera Je [Monastery], he asked Khensur Rinpoche to go to Manjushri Institute to teach. And as I heard it—I didn’t hear this directly from Khensur Rinpoche—but I heard that he said, “Why are you sending all the geshes to teach these people who don’t know anything about Buddhism, who just need to learn like ‘Don’t kill’ and ‘Don’t steal’ and things like this?” Because he’s a geshe lharampa which is like a PhD with honors so it’s a very high educational degree. So, “Why are you sending people like this to the West?” Lama said, “Well, just wait. You’ll see.” And then as I heard the story, a few years later Khensur Rinpoche said to Lama, “I understand now.”

Because we Westerners ask a lot of questions and they’re not necessarily the questions that the Tibetans would ask. So you really need someone who’s quite astute, who knows the teachings very well to be able to dialogue because we come from a completely different set of assumptions. Speaking to a Tibetan audience you don’t need to talk about the existence of rebirth, the existence of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, or karma, nirvana. These things are taken for granted. Westerners go, “Well, what do you mean karma? What’s that?” And, “Buddha, Dharma, Sangha? How do I know they exist? This sounds just like what I was taught as a little kid, ‘Believe in God.’ How do I know there’s such a thing as Buddha, Dharma, Sangha?” So, it’s not easy questions to ask. So you really need someone who is quite astute to be able to handle students like us.

So he taught at Manjushri Institute for a number of years and it must have been in late ’82 or early ’83 that he came to be the abbot of Nalanda Monastery. That’s in southern France. And I at that time was studying, I was at Dorje Palmo Monastery, the nun’s compliment of Nalanda. And we used to go over to Nalanda and have teachings together. So that’s the period from ’82 to ‘85 where I really studied quite extensively with Khensur Rinpoche. And he taught with such incredible joyous effort. It was unbelievable because would teach two 1-½ hour classes five days a week to us. And we were like, “Ughh!” and he was just raring to go.

It was interesting because I knew Venerable Steve from that time too and so this is 20-25 years ago. And Venerable Steve and I somehow were thinking alike had the same questions. Khensur Rinpoche would say something and then his hand or my hand would go up, “But, but, but….” “This, this, this, this.” Always asking questions. So he was incredibly patient with us.

So then he went back to Sera Monastery after about ten years at Nalanda and he’s been teaching there for a number of years. And he became the abbot; he was the abbot for six years. So that’s why he has the title “Khensur Rinpoche.” “Khensur” means the former abbot; and “Rinpoche” means precious. So, it’s a title. That’s not his name; so the “precious former abbot” of Sera Je. Although I wasn’t at Sera Je at that time I’ve heard from a number of people that he was a really excellent abbot and was able to bring about a lot of peace and harmony in the monastery. Because in those days there were some difficulties going on so he was apparently quite skillful in dealing with people who had different ideas.

And then in recent years he’s been traveling a little bit more: he was in Taiwan last year or earlier this year. He’s going to New Zealand after he’s here: so really spreading the Dharma. And quite an exceptional teacher so I really recommend that you take full advantage of studying with him and asking your questions. And Venerable Steve is also quite a good translator. He’s been translating for Khensur Rinpoche for many years so he really knows the language.

Nagarjuna’s life

And then we’re going to be studying the Precious Garland of Nagarjuna. Nagarjuna was one of the early Buddhist sages. The Buddha lived 5th century BCE and Nagarjuna appeared 400 hundred years after that, so that would be first century BCE, and lived for six hundred years. Western scholars say that Nagarjuna appeared late first century/ early second century AD and that there were probably two or maybe even more Nagarjunas: one who taught sutra, one who taught tantra. Regardless, it doesn’t matter. If you look at the meaning of the text, the text is quite profound.

But I thought I’d tell you a little bit about the stories involved in the scriptures involving Nagarjuna. Whether you take them literally or not is completely up to you. But I think they have some kind of purpose behind them too. So it’s said that Nagarjuna—before this lifetime, many eons ago—he was the disciple of another Buddha. He made a very strong determination and vow in the presence of that Buddha because he had great compassion, great altruism, to really spread the Dharma and make the Dharma flourish. And so that Buddha at that time then predicted his enlightenment after so many eons; being born in a certain pure land and becoming enlightened there. And as a result of that vow that he made in that previous life then many eons later he was born in India during the dispensation of Shakyamuni Buddha. And it’s said by those who believe that he lived six hundred years that Nagarjuna came three times on our earth. The first time he was born and he became a monk under Saraha. And he was living at Nalanda and he protected the monks there from famine by doing alchemy and different things. So he worked for the Sangha, the monastic community, in that capacity at that time.

Then he went to the land of the nagas. The nagas are these kind of creatures that are kind of like snakes, but not really. Some of them live in wet or damp areas and they’re said to have great jewels and vast wealth. So he went to the land of the nagas and the reason he did this was that during the time of Shakyamuni Buddha the Buddha taught the Prajnaparamita sutras. And the content of those sutras was quite radical; it was really teaching about the emptiness of inherent existence of all phenomena. And it’s said that the people who were alive at the time of Shakyamuni Buddha didn’t have the mental receptivity to that level of teachings. And so although the Buddha gave them, they were not widely spread and the scriptures were taken to the land of the nagas for protection. So Nagarjuna went to the land of the nagas. Then when he came back, so his second appearance on our earth, he brought back with him the Prajnaparamita sutras and he began to teach those.

And those are some of the sutras that are in the Kangyur. They’re incredibly profound and so much of our tradition is based on them: really presenting the view of reality. And so in this period of Nagarjuna’s life then he taught vastly about emptiness and so many of the texts which he wrote, including this one I think, came from that period in his life.

And then he left the earth again and he went…. I forget where he went that time. But when he came back that time he brought with him some more Mahayana sutras like the Great Drum Sutra, the Great Cloud Sutra, and so on; so bringing even more Mahayana sutras to our earth. And then after he passed away from this life, then was born in the pure land and has or will soon attain full enlightenment there.

What I think is quite interesting, the story, whether you take it literally or not, is that it places a person’s existence over many lifetimes. And it really is an example to us of the power of cause and effect. Because in a previous life this individual out of tremendous compassion for the rest of us, making this vow to spread the teachings; and especially the teachings on emptiness. So due to the force of that mental state, that great vow, that great aspiration, then being born in the dispensation of Shakyamuni Buddha and be able to teach emptiness and leave for us these amazing text that teach the right view and the path to liberation and enlightenment. And then similarly because of that vow, because of his magnificent altruistic deeds in this life, then being reborn in the pure land and attain full enlightenment. So it’s really showing the existence of a person over many, many life times and how what we do at one time of our existence influences what happens at another time in our existence.

And I think this can act as a way for us to look at what we aspire to do. What are the aspirations that we put in our own minds stream? Nagarjuna, motivated by compassion, put the aspiration to benefit all beings by spreading the teachings on emptiness. What do we aspire for? “I aspire to get a good job so I can have a lot of money. I aspire to have a happy relationship and a happy family life.” Look at the kinds of aspirations that come to our mind quite naturally and begin to question them and say,” Okay we’re all making aspirations all the time but look at the aspirations I’m making. Look at the aspirations Nagarjuna made. What are the results of my aspirations going to be? And what we’re the results of his aspirations?”

And then it can inspire us to be a little more careful of what we aspire for. Because we’re planting those seeds in our mind; an aspiration is directing our mind in a certain way. So we have to take care. Sometimes we might aspire, “Oh, may I get even with that person who harmed me.“ What does that do to our mind when we put that kind of aspiration energy to it? What kind of result is that going to bring to us in terms of where we’ll be reborn and what we’ll be able to do in our future lives? And so that’s what I find useful about these kinds of stories. I used to kind of rebel against them, “This sounds like fairy tales. Do they really expect us to believe that Nagarjuna lived six hundred years?” Let’s leave that aside and let’s look more at the point behind it. When you look more at the point behind it there’s some Dharma meaning in there that can really teach us something really important.

Two main themes: high status and definite goodness

Okay so that’s a little bit about Nagarjuna. And in the Precious Garland there are two main themes in the teachings. I don’t know if Nagarjuna wrote it or spoke it but it was a precious garland of advice for a king on how to practice. So the two main themes are what Jeffrey Hopkins in his translation translates it as “high status” but I prefer the translation of “fortunate state” because we’re so status conscious in this country we think that ”high status” means being the president or the CEO and that’s not what’s meant by “high status.” It’s a “fortunate state,” which I’ll explain what that means in a minute. The other theme is what’s called “definite goodness” and that refers to liberation and enlightenment. So here we’re talking about how to make our life useful, the things we can direct our minds towards the future by taking advantage of the potential we have now with our precious human life. “Fortunate state” refers to a good rebirth and actually more specifically any kind of happy feeling in the mind or virtuous state of mind that appears in those with human rebirth or deva rebirths or god rebirths. So that is the happiness within cyclic existence. It’s limited happiness but it’s a “fortunate state” which is the kind of state we have right now.

And then, the other purpose of our precious human life, the other theme of the Precious Garland, is “definite goodness,” which refers to getting free of the cycle of constantly reoccurring problems or samsara, and enlightenment, which is attaining full Buddhahood. So not only freeing ourselves of this vicious cycle but gaining all the qualities necessary to be able to lead others on the path to enlightenment as well.

So those are the two major themes. So in order to understand those themes we have to back up a little bit, okay? And what does it mean to be in cyclic existence? What is this cyclic existence that we want to attain a higher state in? And what is this cycle of existence that we actually want to be free of and to free others from?

What is a person?

1. The nature of the body

Now to understand cyclic existence we have to back up even a little bit more, to what does it mean to be a person? What we label “I”, or what we label a person, is dependent on the body and the mind. So let’s just relate this to our experience. We have a certain name because there’s a body and a mind here, and then rather than saying, “That body over there with those grey hairs and those wrinkles and that mind that has a habit of getting angry is walking down the street.” It’s a shortcut to say Sam or Harry or Susan or Patricia or whoever is walking down the street. So a person is something that is merely labeled in dependence on a body and a mind. So let’s look at what the body and mind are. Body, our society knows lots about bodies. Or at least we think we do when we’re spending many dollars in research trying to learn more about the body. But one thing we do know about the body is that it’s made up of atoms and molecules; it’s material in nature. It has color and shape and smell and it makes sounds, touches and all these kinds of things. We know a lot about the brain. The brain is a physical organ, again color, shape, made of atoms and molecules.

So that’s the nature of the body. And the body has its causes. The substantial cause of our body, the principle thing that became our body, is the sperm and egg of our parents. So actually our body isn’t even ours; it’s actually our parents isn’t it? If you think about it, it’s not ours; it’s the sperm and egg of our parents. But it’s not just the sperm and egg of our parents; it’s all the broccoli and tofu and everything else you’ve eaten since you were born. So that’s what this body is: it’s a combination of all the various elements on the table of elements that we study in chemistry class, that’s all it is. So that the sperm and the egg and all the food that we ate before, that‘s the cause of the body. The body is alive now, we say it’s alive or we’re alive, because the mind and the body are interrelated, they have some connection. When the mind and the body split the body becomes a corpse and it gets recycled, doesn’t it? The body we cherish so much, this body we pamper so much, that we worry about so much, that we spend so much money to make it beautiful and comfortable, basically just gets recycled. And it came from recycled material. It came from the bodies of our parents, which are recycled broccoli and potatoes and everything, too. We laugh at it but this is true; this is all the body is. So it makes us wonder why we’re so attached to it. I mean if there were this pile of just groceries there, would you be so attached to it? “Oh my body you have to be comfortable.” Really that’s just the nature of the body, what the cause of the body is and what the result of the body is.

2. The nature of the mind

The mind is not made of atoms and molecules. It’s not made of the things on the periodic chart. The mind has two qualities. One is clarity, and the other is awareness. Clarity means the ability to reflect objects. Awareness is to engage with those objects. So when we say mind, we’re talking about all the parts of us that are conscious; that reflect and engage objects. So it includes our emotions, our intellect, our sense consciousnesses; the visual consciousness that sees color and shape, the auditory consciousness the hears sound, the olfactory consciousness that detects odors, the gustatory consciousness that taste, the tactile consciousness that feels various sensations, and the mental consciousness which, among other things, thinks and does other various activities. It sleeps and everything else. So we have those six basic consciousnesses, five sense consciousnesses and the mental consciousness.

And then we have all these metal factors, which could be feelings of happiness or unhappiness or neutral. They could be discriminations and they could be all the kinds of emotions we have, all the various attitudes and views that we have. So any kind of conscious aware element of us is all heaped under this big grab bag we call mind. So don’t think of mind and brain as the same thing; they aren’t. The brain is a physical organ, the mind isn’t.

I have the Encarta Encyclopedia on my computer and one day I looked up brain. Pages upon pages upon pages about brain. The I looked up mind; a very short entry. If you ask a scientist what is the mind they usually change the subject. Because scientists don’t’ really know what the mind is. Some of them say that the mind is just an emergent property of the brain. When your serotonin does this and that, and your synapses fire in a certain way, then there’s mind. But I don’t find that very satisfactory. And I asked one of the scientists once, I said, “When I’m upset with somebody, do you think it’s only my synapses that are firing in a certain way?” And he said, “No.” It’s true when we’re upset or when we’re feeling a lot of gratitude or kindness, appreciation towards others that is an internal experiential feeling isn’t it? It’s not just nerves and chemicals, because you could have those nerves and chemicals flashing in your Petri dish and are you going to say, “Oh there’s attachment, there’s love?” No, because those things are experiences that are there in our mind and aren’t made of atoms and molecules. The mind and body have some relationship while we’re alive, don’t they? It goes both ways. When you’re sick then you get in a bad mood more easily. But also, if you’re in a bad mood you get sick more easily. If you’re in a good mood and you have happy mind, you heal better. So the body and mind are related but are not exactly the same thing. When we feel pain or pleasure for example those are real feelings that we have ourselves. They aren’t just synapses and chemicals going on. You wouldn’t look into a dish and say, “Oh, there’s pain. There’s pleasure.”

The continuity of the mind

The same thing, people see dead bodies; our culture tends to hide them away. But when you see a dead body, something is different than a live body, what is it? What’s not there when there’s a corpse? The brain’s still there but the mind is gone. So, while the body is physical in nature and its continuity is physical—it came from the sperm and egg, it’s recycled in nature, 100% recycled material—the mind, the clarity and awareness, isn’t physical like that. It has its own continuity. If we take our mind, like right now in this minute, what is the substantial cause? Where did this moment of mind come from? Did it just appear out of nowhere? No, it came from our previous moment of mind, didn’t it? And that came from the moment of mind before that, and the moment of mind before that. So we have this incredible continuity of moments of mind that just go back and each of these different moments of mind is different.

Is our mind exactly the same right now as it was when we came into this room? No, we’re thinking differently, something is different. What about your mind now and when you were five years old? Big difference. But there’s a continuity there, isn’t there? There’s a continuity between the five-year-old mind and the mind you have now. When we were in our mother’s womb there was consciousness then. We don’t remember it, but we know that babies have consciousness. Even when you were one month old, you don’t remember that, but that consciousness, that mind in the newborn baby, in the fetus, in the womb, also has consciousness. It also is in the same continuity of our present mind stream. So we see that one moment of mind is produced by the previous. One moment of clarity and awareness is produced by the previous moment, and that by the previous moment, and that by the previous, and that by the previous. Now you get back to the time of conception, or whenever exactly it is that the consciousness enters into the sperm and the egg, and that consciousness, that mind at the moment of conception, where did it come from? What was its substantial cause? Did the stork bring it? I don’t think so. Did it just appear due to chemical firings in the brain? No. Until that point each moment of mind had come about due to the previous moment of mind.

So too, that first moment of consciousness in this present life came about due to a previous moment of mind. So the mind existed before it entered into this body and here we get into the topic of previous lives because that consciousness had moments in its continuity and so on. So we can go back infinitely in terms of the mind one moment of mind being produced by the previous moment. Right now our mind is conjoined with this body. When die, death is simply the separation of the body and mind, that’s all death is. It’s just body going one direction the mind going in another direction. At the moment of death the mind doesn’t stop because you have one moment of clarity and awareness preceding the next and so the mind goes on after the death of this body into another life.

Some people say, “Where did it start?” And when they say that, I say,” Where did the number line start? Where does the number line end? Where does the square root of two end? We get into topic called infinity; there isn’t any beginning. So sometimes our mind feels much more secure when there’s a beginning. I want a nice, clean, clear beginning. But things aren’t like that. Let’s say there was a beginning of mind. So you have something over here that’s nothingness and here’s a beginning mind and then after that you have the continuity of mind. So there was some first moment of mind. If you state there’s some absolute first moment of mind then the question comes, “What caused it?” Because if there were no cause then it came about causelessly; it came about with no causes. Does anything that exists and functions happen without causes? No. Everything has to have a cause. So if that first moment of mind had a cause then that wasn’t an absolute beginning of mind; there was cause to it. So Buddhism talks a lot about infinity, we don’t get into identifying a first moment of the universe, the first moment of mind or anything like that. Because logically when you apply reasoning it’s very difficult to identify any kind of absolute beginning like that. And this is regardless whether it makes us more secure to believe in it or not. The reality is we can’t identify something like that.

What are the important questions?

The Buddha was very practical also in this way because sometimes people would come and ask him when was the beginning of the universe and when is the end of the universe—physical stuff. He didn’t answer those questions; he was very practical. He said it’s like you got shot by an arrow. The wound is gushing in blood, but before you went to the doctor you said. “I want to know who made the arrow, and where the arrow came from and how many feathers it had and who shot it.” If you wanted to know all that before you got your medical treatment, forget it, you’re going to die. So similarly he said we are in this situation of confusion, misery in our lives, if we spend all of our time trying to theorize about the beginning of the universe and the beginning of the mind, what’s the purpose? We’re going to keep perpetuating our own misery. Instead what’s important is for us to examine what really is the cause of our unhappiness. What really causes unhappiness?

What really causes unhappiness?

Usually when we think of what causes our happiness–especially in our Western culture—we come up with a whole litany. It starts with our parents. Ever since Freud we’ve blamed everything on our parents which I think is a gross injustice. “Why am I so screwed up? Well because my parents got married too young, they fought, I was the third child and they didn’t like me. That’s the reason.” Or, “My teachers: my first grade teacher didn’t understand me and my third grade teacher made me do what I didn’t want. That’s cause for my problems.” What else cause our problems? “George Bush is the cause of all problems.” And, on a more personal level, what are other causes of our problems: our teachers, our bosses, our partners, our friends, our neighbors?

We’re always blaming something outside. “Why am I unhappy? Because somebody else did this.” So that’s the usual view of the cause of our misery. That worldview is a dead end because if you have that worldview, that happiness and suffering come from outside, then the only way to be happy is to get rid of everybody who bugs you, get rid of all the situations you don’t like and surround yourself with everything and everybody that you like. And that’s the way we’ve been trying to do it since we’ve been born. Always trying to put near us everything that we like, everyone that we like, and get rid of or get away from or destroy everything we don’t like. Have we succeeded? No. So that’s what I mean that that world view is a total dead end. Do you know anybody who has succeeded, anybody that’s 100 percent happy, who has everything they want and nothing they don’t want? Do you know anybody? Can you name one person? You’re going to say, “Princess Dianna.” Do you think Princess Diana was happy? I don’t think so. I wouldn’t want to be Princess Diana. Do you think Bill Gates is happy? He can’t even walk down the street. When you’re rich like that you can’t even do a simple thing like walk down the street. Their kids can’t even go out and play. They’re imprisoned by wealth.

So look. Who do we know who’s everlastingly happy by successfully rearranging everything in their life? It doesn’t work. And anyway we’ve all done this haven’t we? We get everybody around us that we like and then what happens? We don’t like them anymore! (L) They don’t like us! And the person we thought was the most wonderful person who was always going to make us happy, they bug us, they get on our nerves and we want to get free from them! Our minds are incredibly unstable. Aren’t they? And what makes us happy or unhappy at any minute is so changeable. One minute we want this, the next minute we want that.

So we can see this whole world view that happiness and suffering come from outside and therefore I have to rearrange my environment, it just doesn’t work What the Buddha did is he said, “Check up and see if that world view is actually correct or not.” And then he gave us some methods for checking up. He said, “Look at the state of your mind. How does your mind create your happiness or your suffering?”

Looking at our anger

The example is so stark. There is waking up in a bad mood. We’ve all woken up in a bad mood. When I wake up in a bad mood I have what I call free-floating anger. It means that I’m in a bad mood. Nothing happened and I don’t know why I’m in a bad mood. But I’m waiting for somebody to say,”Good morning” so I can get mad at him or her and then I can blame my bad mood on somebody else. They said good morning in a way I didn’t like. It’s become so obvious that when we’re in a bad mood, nothing ever makes us happy. We can be in the most beautiful place but if we’re in a bad mood we’re so miserable. We can be with somebody that we’re very fond of, but if we’re in a bad mood we can’t stand them. It could be we want some kind of acknowledgement or prestige or something and we can get it; but if we’re in a bad mood we don’t enjoy it.

What we’re getting at here is that the state of our mind creates our happiness and our suffering. Similarly, if we’re in a good mood, even if somebody criticizes us we’re okay with it and we don’t get bent out of shape. Even they don’t serve what we like for lunch, if we’re in a good mood, we’re okay. We don’t complain. So much comes from our own mind. Even if we’re not in a bad mood but, let’s say, somebody says something to us and we interpret it as criticism we think, “That person’s criticizing me. They’re making me unhappy and they’re the source of my suffering. Therefore I have to retaliate and I have to say something to defend myself because they are accusing me unjustly.” Because whenever someone gives us feedback we don’t like it, it’s always unfair isn’t it? That’s the primary assumption throughout the universe. “How dare you give me negative feedback? I didn’t do it!” We learned that from the time we were kids didn’t we? “It’s unfair! It’s his fault, not mine!” Even though we did whatever obnoxious thing we did as kids, we always say,” It’s not my fault; it’s somebody else’s fault!”

We get so defensive when somebody gives us feedback we don’t like, even if they’re trying to help us. Even if somebody says, “Please clean the spoon,” we go, “Don’t tell me what to do! Why are you telling me what to do, who do you think you are?” Just watch our minds. We sign up on the chore list in there. “Why do I have to sign up for a chore? Why do I have to put the dishes away?” Our mind is always having so many opinions, so many judgments about everything. And when we have these kinds of opinions or judgments, these kinds of interpretations of our experiences, we become resentful. We become belligerent, angry, upset and unhappy. And all of this is coming from our own mind. It’s one of the things that you really see when you live together in community and it is part of the purpose of the Abbey. We live together and watch how our minds write these incredible stories and gets either ecstatic or upset. And it had nothing to do with the other person at all! It’s our own trip.

Even if somebody says to us, “Oh, you were suppose to do this and you didn’t do it”, and we get upset. Why do we need to get upset? This is the thing I go through when I get angry. I’m angry and then I say,” Why am I angry?” and my mind says, “Well, because he did this and she did that.” And I then I ask myself, “Sure they did those things, but why are you angry?” “Well, he did this and she did that.” “That is true, but why are you angry? Why does somebody doing that have to produce the result of my being angry? Where is that anger coming from? It’s not coming from the other person.” I have a choice whether to be angry or not, and I usually really get into the anger! Rrrahhh!! But then I get miserable afterwards.

Looking at our experience in terms of karma

So we really we begin to see how our happiness and our suffering come from the state of our own mind. Our mind creates our own happiness and suffering. It creates the happiness and suffering in two ways. One way is by what we’re thinking now; how we are interpreting an event right now: we make ourselves happy or miserable. Another way is through whatever motivations we have now. Those motivations, those thoughts or those emotions generate certain actions. Those actions are karma. That’s what karma is: just action of our body, of our speech, and of our mind. These physical, verbal and mental actions leave traces of energy on the continuum of our mind. Those are called karmic seeds or karmic imprints. They’re like predispositions or tendencies to have various experiences. So that’s another way that our mind causes our experience is through the karma that we create. Through the actions that we do we put seeds in our own mind that influence what we experience.

Have you ever wondered, “Why was I born me?” Have you ever wondered that? “Why was I born in this particular family or this country? Why did I have the opportunities that I had in my life? Why didn’t I have other opportunities in my life? Why?” We could have been born as a totally different person: different body, different family, different schooling. Why were we born in this body with its set of circumstances? From a Buddhist viewpoint we attribute that to karma, the actions that we did in previous lives.

So in this present life we’re experiencing the result of a tremendous amount of good karma. We have human bodies and we have a human mind so we can think. We can hear teachings. We have some discriminating wisdom that can tell the difference between what is helpful to practice and what we need to abandon; between what are the causes of happiness and what are the causes of misery. So, just having this human body and mind is the result of incredibly good karma that we’ve created in the past. Having food that we’ve eaten that we’ve taken for granted. It didn’t just come about by accident. We created the karma through being generous in previous lives to have food now. We created the cause for a human body and mind by keeping ethical conduct in the past. If we have a reasonable appearance and we are not tremendously ugly, it’s because of having patience in the past and refraining from anger. So, many of the situations and conditions that we have right now they don’t come out of nowhere. They come out of our past actions.

If we actually look at our life, we have a tremendous amount of freedom and good fortune. So this didn’t happen by chance. And it’s not freedom and good fortune just in terms being able to have pleasure. Because we can experience a lot of pleasure but then where it does go after it’s experienced?

I remember before I got ordained I went back to my parents’ house where I had stored bunch of things. And I went back. Scrapbooks! I had all these souvenirs of all the guys I dated as a teenager, a huge scrapbook with all these napkins and, well, rubbish! So you look at it and it is rubbish of a teenager. But as adults we collect a lot of our own adult rubbish, don’t we?. And, even if it’s not physical stuff, we store up a lot of memories. But the memories of previous happiness are just memories, aren’t they? That happiness is not happening now.

So especially if we had to hurt somebody else, we hurt somebody else or we acted in a very selfish way in order to get some kind of happiness earlier on: The happiness we experienced and it’s gone—but the karmic imprints from doing those actions that brought about getting what we wanted? Those karmic imprints are still on our mind stream and they’re going to influence what’s going to happen to us.

When ever we have some kind of misery in our lives we always go, “Why me?” We never do that when we have happiness. After breakfast this morning none of us went, “Why me? Why did I have the good fortune of having breakfast this morning when so many people are starving?” None of us. Did you think that this morning? We just spaced out. We take it for granted, but it didn’t happen by accident. And it’s incredible, the good fortune that we have. But the moment some small harmful thing happens, we stub our toe, “Why me?”

So any negative thing happens and it’s, “Why me? I have this suffering nobody else does.” And then we get into a big pity party. “Poor me, poor me.” And we really get into it which of course makes the situation worse. But we get a certain kind of ego pleasure from feeling sorry for ourselves, don’t we?

So we begin to see that when we have happiness in our lives it’s not coming from out of nowhere. It’s due to our previous actions, which depended on the mind that motivated them. And when we have suffering now, it depends on our previous karma that depended also on the previous minds that did those actions, that planted those karmic seeds, that ripened into the misery that we’re experiencing. And we also begin to see that how we react to whatever happiness or misery we have now either increase that happiness or misery or decrease it. That even though karma is ripening from the past, how we react to our situation now creates our happiness and suffering now; and it also creates more karma for the future.

Working with negative karmic results

So let’s say I want something really bad and I don’t get what I want. And then I get angry and resentful because the world is always unfair to me and everybody else has good things but not me. And I get stuck in my anger and my resentment or maybe my jealousy, “Oh, they always get it and I never do.” Then those emotions make us miserable right now and because they lead us to plotting revenge or throwing a pity party or moaning and groaning about our life. Then those same mental states just lead us to create more and more negative karma which creates more and more suffering in the future.

Where as if we have a ripening of negative karma, we’re unhappy right now but we say, “Oh, this is a ripening of negative karma. That’s good that that karma of the past ripened and now is finishing. It is over and done with. It could have resulted in many eons in an unhappy miserable rebirth but it didn’t.” “So I have a headache right now, well, that’s manageable.”

So a lot of our misery, “Oh this is unbearable!” But when you think that it could have ripened in a horrible rebirth then all this misery is quite bearable: “I can make it through this one.” If we think like that then our mind become happy now and we don’t get involved in more negative karma by moaning and groaning and being bitter and unhappy. Instead we’re able to switch our minds, so the mind is happy now. And then we’ll engage in more actions, that even though we experience some suffering, we’ve become much more compassionate and helpful to other people, because we understand what their situation in a much better way. So that compassionate attitude and the actions that flow from it create more good karma. So we might experience the ripening of a negative karma and from that we can either create either more negative karma or we can create positive karma.

In a similar way we can experience the ripening of positive karma and totally space out: like we did about breakfast. Especially if we just look at breakfast,” Oh, there’s good food I like that.” Gobble, gobble, chomp, chomp, and chomp! Sometimes we’re like that around food. We are kind of like animals. You know how dogs and cats just SSSlluuurp. I love to watch in cafeterias, people start eating the food even before they’ve paid for it. Just the mind is like totally fixated. So there’s a ripening of good karma; but maybe that person is taking what hasn’t been freely given to them by taking the food. Or maybe they’re having a very greedy mind while they’re eating. Or maybe they’re feeling arrogant, “Oh, I have all this good food. What about those poor slobs on the earth who don’t have.”

So the reaction to our good karma could be very varied. So if we react with some kind of self-centered motivation, then that could easily lead us to being or having more deception or stealing or cheating in some way to get more things that we want. Or if we have a ripening of good karma we could respond with: and this i why we do the prayers before we eat. We respond with: here’s the food and we offer it to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. Or we offer it to sentient beings so that they can make offering to Buddha, Dharma, Sangha. We eat with mindfulness and a feeling of appreciation for all those who gave us the food. And so from that, that creates a lot of good karma which leads to happiness in the future.

Our mind at death

So we can see that what we experience now is the result of the past. But what we experience now also leads us to create the causes for what we’ll experience in the future. And that’s why it becomes so important to pay attention to what’s going on in our mind. Because at the moment of death, what’s going on in the mind is going to determine where we’re reborn. So if we die and at the time of death we’re very angry let’s say, “Why do I have to die? This is unfair. Medical science should have devised a way to cure me. I should be able to live long.” Or “I’m so miserable, why do I have to suffer like this?” And having a lot of anger; then that anger creates…. It’s like a fertilizer that makes some negative karma, that we created previously, ripen. And when that negative karma ripens then it distorts the way our mind perceives things. And all of a sudden, “Wow, being born as an animal looks good!” and before you know it we’re in the body of a donkey. Or we’re in the body of a grasshopper or something like this.

So there are these different realms of existence. The animal realm we can see but there are other realms of existence. There are hellish beings, there are hungry ghost who are always dissatisfied. And those come about by the power of our mind and what our mind is familiar with. So if we have a mind that is always craving, craving, craving and always dissatisfied; well, that’s kind of like the mind of a hungry ghost. We get reborn like that. If we spend a lot of our life creating fear in others and having a lot of malicious thought and ill will towards others, we create the cause for a hellish existence in our own mind by the power of what our mind is thinking about.

In a similar way at the time of death if: let’s say we take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, or let’s say we generate love and compassion, then that sets the stage for a constructive karma to ripen. So maybe the karma from making offerings to the Three Jewels; or maybe the karma of being kind and serving others; or maybe the karma of really helping others, taking care of others; then that karma ripens and that makes our mind attracted to a good rebirth as a human, or in a celestial realm as a deva or a god.

So none of these realms where we get reborn in are permanent; they’re not permanent lives just as this life is not permanent. It doesn’t last forever. So as long as the karma or the causal energy is there to live in any particular body then our consciousness is conjoined with that body. When that karma runs out then the body and mind separate and the mind goes on.

Now we get reborn again and again because we’re under the influence of ignorance. We misapprehend the deeper nature of how we and everything else exists. So that ignorant mind lies at the foundation of our constant rebirth in the cycle of existence or samsara. So initially in our practice what we’re trying to do is get a good rebirth, because that’s the most urgent thing. Let’s just at least in the next life stay out of the really bad rebirths. So that’s why the aspiration for higher status or fortunate states comes first, it’s the most urgent thing. But then as our mind expands we want to look beyond that. And we see that even if you get a good rebirth next time still we’re born under the influence of ignorance, clinging attachment, and anger. And so we still have no freedom. The mind is controlled by these three poisonous attitudes.

So at that point we say, “Well, wait a minute! What causes these three poisonous attitudes and is there an antidote to them?” We see how they’re rooted in ignorance; how wisdom is an antidote to ignorance. And then we generate the aspiration to be free of cyclic existence and attain nirvana or liberation. So that’s the beginning of definite goodness: the second theme in the text. And then as our mind expands further and further: it began by thinking about, “Let’s get myself out of cyclic existence.” As our mind expands then we think, “Well then what about everybody else? They’re all exactly like me wanting happiness and not wanting to suffer. How about helping everybody out of cyclic existence?” And when we do that that leads to generating the bodhicitta, the altruistic intention to become a fully enlightened Buddha in order to benefit all beings. And that’s the second aspect of definite goodness.

So that’s a little bit of an introduction. I speeded it up at the end because we have to stay on schedule. But there’s tomorrow, if we’re alive and we can continue on then and go into the subject a little more.

Questions and answers

So maybe we have time for a few questions.

Audience: From the Buddhist perspective is the mind in the heart?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Is the mind in the heart? The heart: you mean the one that pumps? Some people think that the mind is in the brain. Actually the mind permeates the entire body. When the time of death comes the mind absorbs: as the body is not able to support the consciousness anymore, then the mind absorbs and dissolves into the center of the heart in the center of our chest. And it from there that it departs to the next life.

Audience: This has puzzles me all my life. If there is a continuation, how come there is not a steady state of human souls. Are there other realms?

VTC: So your question is how come the human population on earth is expanding? Because there’s a whole big universe where you can be reborn. And there are many realms of existence. And human beings are actually quite a minority on this planet. We’re a little bit arrogant thinking we control the planet because there are many more animals and insects, aren’t there? And, in addition to this, there are many places in this universe to be born, many places in other universes. Planet earth is very tiny actually.

Audience: Does one moment build on the previous moment? I ask because as we get older we seem to get so much smarter.

VTC: So does one moment build on the previous moment because as we get older we get smarter, contrary to what we thought when we were teenagers? We thought we knew everything then and the adults were dumber. Yes, one moment does build on the next. But whether we get smarter depends on us. Because some people, you can see in their lives that they make the same mistake again and again. They don’t seem to learn from their mistake; whereas if we can really make peace with our past and learn from our mistakes, then one moment builds upon another in a very wonderful way.

Audience: If the two qualities of the mind are clarity and awareness, why is there a lack of continuity in what we can remember; like when the mind separates from the body at death?

VTC: So why we can’t we remember previous lives or why can’t we remember where we put our car keys a half an hour ago? Why is there that break in awareness? Well, the mind is just aware of other things. Or sometimes it might be aware of a clear state. So we can’t remember. The mind is always aware of something but it could be distracted by something else. And also our mind is very, very obscured. It’s tremendously obscured. We learn things and we notice this a lot as we age, don’t we? You hear something and five minutes later it’s gone, gone. Okay? So the mind is obscured. Or even we learn something when we’re young, we can’t understand it; the mind is obscured. It’s obscured by these afflicted mental states: what’s sometimes called delusions, or afflictions, or disturbing attitudes and negative emotions. And it’s also obscured by a lot of the karma that we’ve created in the past. So the mind has the opportunity, the ability to reflect things, but it’s obscured so it can’t sometimes.

Let’s just sit quietly for a couple of minutes and digest what we’ve heard and think about how to apply it in our life.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.