The truth of the origin of suffering

The truth of the origin of suffering

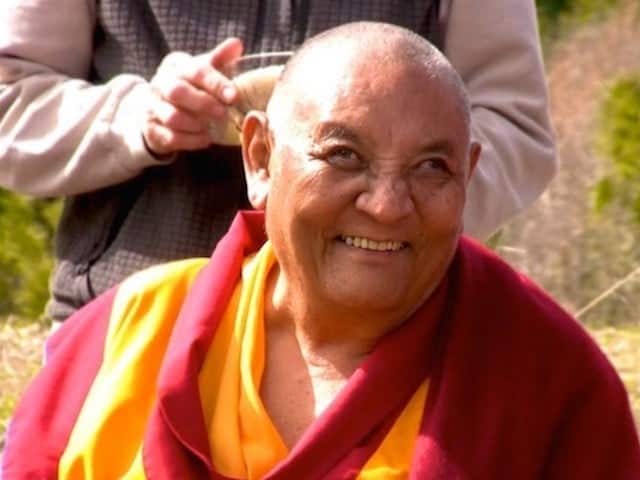

From December 17 to 25, 2006, at Sravasti Abbey, Geshe Jampa Tegchok taught on A Precious Garland of Advice to a King by Nagarjuna. Venerable Thubten Chodron complemented these teachings by giving commentary and background.

- Fortunate states as humans or gods and definite liberation—full enlightenment

- The first two noble truths: dukkha/suffering and its causes

- Inappropriate attention

- The four distortions and how they operate in our minds

- Seeing the impermanent as permanent

- Seeing the unclean as clean

- Seeing what is suffering or dukkha as happiness

- Questions and answers

Precious Garland 04 (download)

Motivation

So let’s cultivate our motivation. From the time we are born we’ve been the recipient of kindness. We couldn’t have survived as infants or toddlers without the kindness of others. We wouldn’t have learned all that we have learned without the kindness of those who taught us. And we wouldn’t be able to use our various talents without the encouragement and the kindness of people who support us. So it’s important to let this enter our field of awareness and enter our heart: that we are the recipient of a tremendous amount of kindness—and have been our entire life. And as we feel that, then automatically the wish arises to return kindness. It seems like the only natural thing to do.

So when we think of the best way to benefit others, (out of the many ways that there are to return kindness), developing ourselves spiritually in the long run is the best way to do that. Because while we may give people food and clothing and shelter and nurse them when they’re ill—and we should do those things—this does not relieve them from the condition of being in cyclic existence. But when we’re able to share the Dharma with them and encourage and lead them on the path: that will show them how to attain fortunate states and definite goodness. And the latter—liberation and enlightenment—which are the cessation of all dukkha, will bring them lasting peace and bliss. And it’s for that reason that we cultivate the bodhicitta motivation: that aspiration to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all beings.

So contemplate that and cultivate it now.

The origin of suffering: inappropriate attention

So as Geshe-la has been mentioning the major themes of the Precious Garland are fortunate states, in other words, rebirth as humans and gods and all the happy feelings that arise in them; and the definite goodness, liberation from cyclic existence and full enlightenment. And so along that line of the last few mornings we’ve been talking about the first two Noble Truths in particular, we’ll get to the last two. But we’ve been talking about dukkha, what is commonly translated as suffering, (but that’s not a very good translation: so, unsatisfactory conditions) and then the second Noble Truth, the cause or origin of them. Because the more we’re able to understand these two then the more we aspire to be free from them. And the more we understand, especially because of the dukkha and how it operates these—negative mental states—then the more we understand how they operate, the more we’ll be able to be aware when they arise within us and then apply the antidote. Whereas if we don’t understand what they are: then we can’t recognize them.

Some people come to Dharma teachings and say, “Oh, you’re always talking about ignorance, anger, hatred. Why don’t you talk about love and compassion? Jealousy and self-centeredness: why do you always talk about this stuff?” Well, it’s because if there’s a thief in your house, you have to know what the thief looks like. You know, if you have a bunch of people in your house and stuff is going missing but you don’t know what the thief looks like the you’re not going to be able to kick him out. So learning about these things that disturb our mind are like learning what the thief looks like. Then we can catch him and kick him out. Otherwise he’s just going to steal all our happiness and keep on doing it.

So I thought to elaborate a little bit more in the context about talking about the origin of suffering. This whole thing of “tsul min yi che” which is the Tibetan for “inappropriate attention” that Khensur Rinpoche was talking about yesterday afternoon. And inappropriate attention is not the same mental factor as attention that is one of the five omnipresent ones that come in all the cognitions. Because I remember asking Geshe Sopa this one time, because this expression “yi che,” and especially “tsul min yi che” it comes in so many different contexts. And I was always thinking, “Oh, there always just that mental factor.” And then he said, “No. No. No. No.” Because you have “yi che,” this mental factor when you talk about the development of calm abiding; then you have the inappropriate attention when you talk about the cause of dukkha. So it comes in many contexts. So it’s one of those words, like we’re noticing, that has many definitions and many meanings according to the circumstance. So it’s just helpful to be aware of.

When it is our own native language we are fully aware when things have different meanings at different times and it never bothers us. But when it’s another language and especially when we are trying to learn technical terms, then it’s like: “That’s the definition. It can only mean that in all circumstances!” Then we get ourselves all tangled up because any language has different meanings for the same word in different situations.

Inappropriate attention as the four distortions:

There’s one way of talking about this inappropriate attention where they’re called the four distortions. And I have found this teaching especially helpful in my practice. So it’s four ways in which we perceive or apprehend things in a distorted manner. There’s some discussion about whether these things are innate afflictions, in other words ones which have been with us since beginningless time; or whether they are acquired ones, in other words afflictions that we learn in this life. Personally speaking I think that they definitely are innate and that also we build them up through acquiring them also during our lifetime; through different psychologies and philosophies build them up. So I’ll explain this a little bit more as we go along.

But in brief, these four are: First, seeing what is impermanent as permanent. Seeing what is unclean as clean. The way it’s translated is like this but I’d like to find some other words for that, when we get to the explanation maybe you can help me. Then the third one, seeing what is dukkha as happiness. And then the fourth, seeing what lacks a self as having a self.

So, we’ll study all about these four but the real thing is to see how they operate in our mind because we have them and they cause so many problems.

1. Seeing the impermanent as permanent: gross and subtle impermanence

So the first one, seeing what is impermanent as permanent. Here impermanent means changing moment by moment. It doesn’t mean come into existence and go out of existence: like the table is impermanent because one day it ceases to exist. No, we are saying here that impermanent has a very specific meaning: it changes moment by moment. So something according to the Buddhist usage of the word can be impermanent and also be eternal. Eternal means it doesn’t cease, the continuum of it doesn’t cease, even though it’s changing moment by moment. So for example, our mindstream: our mind is changing moment by moment, but it’s also eternal it never goes out of existence.

So things that are conditioned, things that arise due to causes and conditions, they are impermanent, they are transient by nature. They arise, abide, and cease all in the same moment. Anything that arises is automatically going out of existence at the same time. So things are momentarily transient. That’s the subtle level of impermanence.

There’s also the gross level of impermanence that we can see with our eyes. The subtle level we can only know through meditation and our mental consciousness. But the gross impermanence is like somebody dying or our favorite antique crashing and breaking; something that is a very gross cessation of something.

We can talk about it and we all say, “Yes. Yes. Everything is impermanent.” But how do we go about living our lives? When somebody dies we’re always surprised aren’t we? Aren’t we? Even if they’re old, even our grandparents or somebody who is very elderly, even when they die we’re always somehow surprised, like, “That’s not supposed to happen!” Aren’t we? So there’s an example of gross impermanence. We don’t even live our life as if we really believed in it because we’re always so surprised. When our car gets in an accident or it’s dented or something, we’re so surprised, “How can this happen?” Well, of course, something that comes into existence isn’t going to stay that way all the time. When a house falls down, when a leak in the pipes happen under your house in the middle of winter, you’re always surprised.

[Feedback from the microphone makes a loud sound] So you see, that’s a very good example, it happened just at the right time. You know, “What’s that? That’s not supposed to happen. Things are supposed to work perfectly all the time.” Our mind has a real difficult time even with this gross level of change. You buy new clothes and then there’s spaghetti sauce all over them after your first meal. Or you put down new carpeting and the dog poos on it. We’re so surprised by these things. And that’s just the gross level.

Now the gross level of impermanence couldn’t happen unless things were changing moment by moment by moment by moment.

Another example of the gross level of impermanence is the sun sets. We see it with our eyes, the sun sets. It rises in the east, sets in the west. But imperceptively, moment by moment, it’s changing across the sky and we aren’t always aware of that. But it never remains the same moment by moment. In the same way, everything in our body is in constant change. The scientists tell us that every cell of our body changes every seven years. So we’ve been totally recycled every seven years. But we don’t even see that level of gross impermanence let alone just the fact that everything in our body is constantly changing. We’re breathing, and the bloods flowing, and all the organs are doing all their different things. Everything’s changing. And even within a cell all the atoms and molecules are changing all the time. Even within an atom, the electrons are moving around and the protons are doing their thing. You know, nothing is stable from one moment to the next.

What is stable and secure?

But this inappropriate attention, this distortion we have in our mind is we see things as very stable. We see our life as stable. We see this planet as stable. Don’t we? We see everything as very stable. Our friendships are supposed to be stable. Our health is supposed to be stable. We have all these plans and they’re all supposed to happen because the world’s supposed to be predictable and stable. But meanwhile our own experience is whatever we plan doesn’t happen. In every day we have an idea of how the day is going to go; and inevitably things happen that we didn’t expect and what we thought was going to happen didn’t. And yet we still continue to believe that things are predictable and secure and stable. You see how that’s a distorted state of mind? And it also causes us so much misery in our life. Because when people die all of a sudden we are totally shocked. Like, “Oh my goodness, they were healthy one moment and dead the next!” But their body is changing moment by moment, and aging and sickness and all that’s happening. Still we’re surprised.

So they say what grief is, grief is adjusting to change that we didn’t expect. That’s all the grief process is. You don’t have to think of grief as hysterically sobbing your eyes out. But it’s just an emotional process of adjusting to change that we didn’t expect. But when you think about it, why didn’t we expect those changes? Why didn’t we expect them? We know that where we live is unstable, we know our friendships are unstable, our relationships are unstable. We know our lives and our friend’s lives are unstable. We know it intellectually but we don’t know it in our own heart because we’re so shocked when that happens.

So some meditation on impermanence is the antidote to this kind of distortion. We meditate on gross impermanence, the meditation on death. And that’s very helpful for helping us to set our priorities in life and in seeing what’s important. And then we meditate on subtle impermanence as a way to really understand how things, compounded phenomena, actually exist; and to see that there’s nothing stable in them. And therefore relying on them for happiness is putting our eggs in the wrong basket. Because anything that is compounded, in other words, created by causes and conditions is going to go out of existence. It’s unstable by its very nature because it exists only because the causes exist. And the causes themselves are impermanent or transient. When the causal energy ceases that object ceases. And moment by moment actually, the causal energy is changing. It’s ceasing.

What is a stable refuge?

So the more we can be aware of even the subtle impermanence, the more we’ll see that taking refuge in things that are created by ignorance, anger, and attachment; things that are conditioned by these defilements are not reliable sources of happiness and refuge. Because right now, what do we take refuge in? What do we think is the source of happiness? Our three jewels in America: refrigerator, the television set, and the credit card. Actually we have four jewels, you know, the car. So this is what we take refuge in. You know, “Every day I go for refuge until I am enlightened in the refrigerator, the television, the credit card, and the car. I will never abandon my refuge in these four.” And then we find so many difficulties in our life.

So if we realize that all those things are changing moment by moment, that because they are created phenomena, they go out of existence. That they don’t remain even for one moment, they’re momentarily changing. Then instead of turning to them for refuge, we’ll begin to think about what is a more stable sense of refuge. Where can we find some kind of actual security? What is conditioned and created by ignorance, anger, and attachment is not going to be a stable source of happiness. When we really meditate on this then it changes the direction our life takes in a very distinct way. Because instead of putting our energy towards something that by its nature is never going to be secure and stable; those of us who want security, which I think is all of us, we’re going to change our approach and look for what is stable. And that is nirvana. That is the ultimate nature of reality: emptiness is a permanent phenomena, meaning it’s not conditioned. It’s the ultimate mode of existence. It’s something that’s secure and stable when we have the wisdom realizing it.

Other names for nirvana are “the unconditioned” and “the deathless.” So those of us who are seeking real security in life, if you want real immortality, look for the deathless. Not for the nectar that’s going to bring you immortality because the body is by nature changing; but the deathless—the ultimate state of peace—the unconditioned nirvana.

So we can see how if we meditate on impermanence it helps us be much more realistic in our life. We’re much less surprised by change, we’re much less shocked and stressed and grieving by change. And instead we learn to shift our attention to ask our selves, “What is real security?” And we see that liberation from cyclic existence is real security. Enlightenment is real security. Why? Because they’re not conditioned by ignorance, anger, and attachment. They’re not created and destroyed moment by moment like that.

That’s the first distortion.

2. Seeing what is unclean as clean

The second one is seeing what is unclean as clean. Like I said I don’t like the words “clean” and “unclean.” But what this is getting at is especially and particularly looking at our body here. We build up the body as something quite miraculous; our whole “body is beautiful.” And go to the beauty shop. And go to the barber shop. And go to the gym. And go to the spa. And go to the golf course. And go to this, and go to that. Dye your hair. Shave your hair. Grow your hair. Have Botox. Whatever it is.

So we’re seeing the body as something that’s beautiful. But when we look at the body in more depth, the body is basically a factory for producing poo and pee. Okay? If we look at what comes out of all our orifices none of it is very nice, is it? We have ear wax, and we have the crusty stuff around our eyes, and we have snot, and we have spit. We sweat. Everything that comes out of the body is not stuff we want to hang around a lot! Isn’t it?

It’s very important to explain here that we’re not saying that the body is evil and sinful. Repeat! And this is on tape! We’re not saying the body is evil and sinful. Do not go back to being five years old and Catholic in Sunday school. We are not saying that. There’s not this kind of thing that the body is sinful and evil in Buddhism. It’s more: let’s just look at our body and see what it is. Because we’re so attached to this body and that attachment brings us a lot of misery. So, let’s see if this thing that we’re attached to is really all that it’s made out to be. And when we look at our body and you peel away the skin, it’s nothing very beautiful is it? And so what’s the use of being so attached to it?

When the time of death comes, why do we cling onto this body? It’s nothing that is that great. When death comes, let go of it. When we’re alive, why are we so fearful about what happens to this body? Why do we worry so much about how we look? You know, we always want to look good and present ourselves properly. Why? The basic nature of this body is intestines and kidneys and this kind of stuff.

Why are our minds so occupied by sex? And why the TV, and the computer, and everything makes such a big deal about sex? I mean, it’s just this body that’s really not so attractive.

Seeing an autopsy in Thailand

In Thailand they have the practice there: the hospitals make it very easy for the monastics to go and see an autopsy. And so when I was in Thailand last year I requested the abbot of the temple where I was if he could arrange that. And he did. And we all went to see an autopsy. And it’s very sobering. You look at that person’s body and you realize your body is exactly the same. And you watch it getting cut open, and all the blood and the insides.

I’ve always found it so amazing that people worry about their body after they die, as if they still have the body. I mean when you die you’ve left it. So who cares about it; but people so attached to what happens to their body after they die. I don’t know. I’ve never quite understood that. And when you see the autopsy; I won’t go into a lot of details but I have pictures if you want to see. It’s quite good for your Dharma practice to see these things. When they cut open the body and they take out the different organs, they weigh them in the scale; just like the scale you have in the grocery store. They’ll cut out the brain and pop it in; they’ll cut out the liver and pop it in. And then they have a knife which is just like a kitchen knife; and they’ll take out the brain and go: cut, cut, cut, cut, cut. Cut, cut, cut, cut, cut. Just like somebody chopping vegetables. Seriously! And then put a little bit in a tin with formaldehyde. So they’ll do this for the various organs. And then at the very end, because they’ve taken out the brain and cut here and opened here; then after they’ve looked at all the organs and decided the cause of death, then they just stuff everything willy-nilly back into your middle. They don’t put the stomach back where it belongs and the lung back where it belonged. They don’t put the brain back here. At the autopsy I went to they put newspaper inside the skull. And they threw the brain and everything else in the middle of the chest. All just, stuff it back in. Take out the needles. Sew it up. And they’re kind of stuffing to get it all in, and squishing to get it all in. Sew it up and there you are.

And this is this body that we think is so precious, so protected. Everybody’s got to respect it. It’s got to look nice. It has to be treated well and always comfortable. We’re so deluded about our body, aren’t we?

So we can see how seeing the body in this distorted way actually brings us a lot of suffering, doesn’t it? Because it creates a lot of attachment to our own body, and then it creates a lot of attachment to other people’s bodies. And then our minds especially when we’re sexually attached to someone else’s body, then our mind: all you can do is run these sexual movies in your mind thinking about other peoples’ bodies and this and that. And what is it?

I remember one time when I was in Dharamsala seeing some pigs and thinking, “Wow, you know, pigs are sexually attracted to each other.” And the idea of being sexually attracted to a pig is like, “Ugh!” I mean, male and female pigs; they just think that they’re so beautiful. And I was thinking, “What’s the difference between human beings when we’re sexually attracted to somebody?” It’s the same kind of thing that the pigs have for each other. It is, isn’t it? I’m not making up stories. It just really hit me: we’re like these pigs that are climbing on top of each other. Yuck. So we laugh but think about it because it’s true, isn’t it?

So we can see how all this brings so much upset and turmoil in our minds. The mind isn’t peaceful because we exaggerate what the nature of the body is. When we’re able to see the body more accurately for what it is, then there’s much more peace in the mind. So like I said, it’s not an aversion to the body: “the body is sinful and it’s evil and let’s punish it,” and this kind of stuff. Because that kind of view does not bring any kind of happiness at all. And it doesn’t solve the mental problems. The Buddha did six years of ascetic practice only eating one grain of rice a day to torture the body and calm the passions of the body. And after six years he realized that it didn’t work. And so he started eating again. And then he crossed the river and sat under the Bodhi tree and that’s when he got enlightened.

So we’re not having a negative attitude towards our body, we’re just trying to see it for what it is. We’re trying to see everything for what it is. Because when we see things for what they are, then we understand them better and our mind doesn’t get so out of whack in relationship to them.

Then also you realize you don’t have to spend so much time trying to look good. It really saves a tremendous amount of time if you don’t worry about your appearance. My niece who’s now twenty-something, when she was seven years old already at that age she was so aware, “Why do you wear the same clothes everyday?” At seven years, “Why do you wear the same clothes everyday?” as if that were something illegal or unthinkably immoral. And it’s actually quite nice: you wear the same clothes everyday; everybody knows what you are going to look like; you don’t worry whether they’ve seen you wear that outfit before, because they have. They can find you in an airport very easily. It’s very nice. You don’t open your closet and spend 15 minutes mentally trying everything on to decide what you want to wear because the decision is already made. And similarly in the morning when you get up, you don’t have to worry about your hair. And you don’t have to worry about showering and your hair being wet and catching cold; and how are you combing your hair; and, “Oh no. There’s more grey hair.” And “What am I going to do? I’d better dye it” and this and that. And you know the guys, “I’m losing my hair, I’d better do something to get more of it.” You just don’t have any! It’s very easy. It’s very easy. You save so much time in the morning.

So, more accurate view of the body; seeing it for what it is.

3. Seeing what is dukkha as happiness

Then the third distortion is seeing what is dukkha, or unsatisfactory in nature as happiness. And this is a real big one for us because yesterday when we were talking about the dukkha of change, how what we call happiness is actually just a gross kind of suffering when it’s very small. Remember, after you’ve been standing for a long time, when you sit down; the misery of sitting down is very small. And you’ve ended the misery of standing up so you say, “Oh, I’m so happy.” But the more you sit down, then your back huts, your knee hurts, everything hurts so you want stand up. So that fact of sitting down is not ultimate happiness because the more you do it, actually the more it’s going to be painful.

Or you come home from work and, “I’m so exhausted. All I want to do is sit in front of the TV.” Or sit in front of the computer, “I want to visit My Space.” Or just surf the computer, looking at this, looking at that. And we think that’s happiness. But if you do it, and do it, and do it, then at one point you’re so miserable. And you just want to be free from it. So that’s what we’re talking about here. Those things that by their nature don’t bring everlasting happiness, by their nature they’re unsatisfactory. But we see them as happiness and therefore we get very attached to them. And we spend a lot of time planning and daydreaming how we’re going to get all those things; thinking that when we have them we’re going to be happy. But in fact, we aren’t.

And I think that this is the real angst of middle-class America: that we work so hard to get all these things and they’re supposed to make us happy and they leave us feeling very blah. It just doesn’t cut it. We’re supposed to be happy—when you have a house, and your mortgage, and your 2.5 children. Although now I think it’s more like 1.8 children, or whatever it is.

When you have all this stuff that you’ve been told is happiness and then you realize that you’re still unhappy inside, there’s still discontent; then we get so confused, and so miserable and depressed. And I think this could be one of the reasons that there is so much depression in this country—is because people are told, “If you do this you’re going to be happy.” And they do it and they aren’t happy. And nobody ever told them, “Hey, this is the nature of samsara, you’re never going to be happy dong this.” So they’re expecting to be happy. They aren’t and then so much depression comes.

When we see things more accurately for what they are then we don’t get so attached to them. When we don’t have so much attachment and craving, then our mind is so much more peaceful. Now initially when people come to the Dharma they say: “No attachment. No craving. Your life is going to be so boring. You’re just going to sit there all day.” “Oh, noodles again for lunch, yeah, sure.” “You’re not going to have any ambition in life.” “But you really need this ambition and this seeking for more and better and wanting to get pleasure and that’s what gives you the thrill in life.” Well, that’s a very nice philosophy that we’ve made up but look and see if it’s true. Does going out to a different restaurant every night really make you happy? People spend a half an hour talking about what to order at the restaurant. It’s amazing. And then when the food comes they eat it quickly while they’re talking to each other and don’t even taste it. But they spend a half an hour or 45 minutes deciding what to order. Is that happiness? No, that’s not.

So our mind, all these things that we get obsessed by, especially when we get competitive, “So and so has that, I want that too.” Now of course we’re all too polite to admit that we try and keep up with the Jones or keep up with the Lobsangs, but in fact, we are. We’re always kind of competing, “Oh, they have that. I want that too.” But does it really make us happy when we get it?

Cultivating contentment

By relinquishing all this craving we’re not relinquishing the happiness. We’re actually creating a condition that is going to allow us to be more content. Because contentment and satisfaction is not dependent on what we have, it’s dependent on the state of our mind. Somebody can be very wealthy and very discontent. Somebody can be very poor and very content. It depends upon the mind. Whether we have the object or not, is not it. It’s whether our mind is content, whether our mind is free of the craving that’s going to determine whether our mind is peaceful and tranquil. Not whether we have it or don’t have it. And so that’s why we see attachment as something to be eliminated on the path; because it disturbs the mind. And attachment is based on seeing what is dukkha by its nature, as actually happiness.

So sometimes people say, “Oh, Buddhists aren’t going to have any ambition if they aren’t craving for more and better.” Well, you do have ambition. You have ambition to develop equal-hearted love and compassion for all sentient beings. People initially think, “Well, if you don’t want more money, and you don’t want a better house. And if you don’t want more fame and a better reputation, and if you don’t want to go on better places for vacation, then you’re just sitting like a bump on a log going, “Dah” all the time. You don’t want to do anything except sit there and go, “Dah,” because you don’t have any attachment. That’s not it at all you know. I mean you look at Khensur Rinpoche is he somebody who strikes you as having a boring uneventful life, and he’s just sitting there going, “Dah,” all day? No. I mean you can see he’s very vibrant. He’s enthusiastic about life. So he has “ambition,” but it’s an ambition to benefit sentient beings. It’s a desire to be of service and to improve one’s mental state and realize the nature of reality and make a positive contribution to society. So yes, Buddhists have a lot of things we do and our lives can be very vibrant. You don’t just sit there all day.

But you can see that this lack of attachment does bring more tranquility. You know when they blew up at Bomyand in Afghanistan those ancient Buddhist statues that were carved into the wall. Can you imagine if it had been either some kind of Muslim religious symbol or a statue of Christ? I mean the Christians would have gone bonkers! The Muslims would have gone bonkers! Did the Buddhists riot? No, nobody rioted. Nobody shot anybody else because the statues were being destroyed. Nobody hijacked an airplane or took hostages. So I think this view of not being attached to external things can bring much more peace and tranquility. And then so that’s the third distortion.

To be continued

And then the fourth distortion is seeing things that … oh, I just realized that it’s time to stop. Oh, I’m dangling a carrot. Let’s do have a few questions and then we’ll do the fourth distortion tomorrow. Any questions?

Questions and answers

His Holiness and Tibet

Audience: More an observation than a question: I’ve always wondered why the Dalai Lama doesn’t try harder to make people aware of the political situation in Tibet. And your explanation of attachment made it clear to me that his purpose is to benefit sentient beings, not to be a political pawn in a material way. That really answered some questions in my mind.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): I think many people wonder that: why doesn’t His Holiness do more for the situation in Tibet? Actually one time somebody asked me, “Why doesn’t he encourage people to revolt and have an armed uprising?” And it made me think: if you look at the situation of the Palestinians and the Tibetans, the late 1940’s and early 1950’s very similar things happened to both of those people. They both lost territory, many people became refugees. If you look at the Palestinian situation how many people have died in the struggle for a Palestinian country? If you think about it, it’s incredible the number of people who have died, have been injured, whose lives have had so much suffering in this attempt to have their own country. You look at the Tibetan situation: there was no armed uprisings, no hijackings, no hostages, no suicide bombers; so many lives weren’t lost because of it. And yet still right now, what is it, 56 years later? Neither of the people have their own country. The result is kind of still the same. But how many peoples’ lives were affected by the anger in the Palestinian movement and how many peoples’ lives were saved because of the pacifist thing in the Buddhist movement? So I think that there’s something quite noteworthy about that.

I once saw an interview, somebody I think from the LA Times was interviewing His Holiness, this was several years back; and saying, “There’s genocide in your country, there’s nuclear dumping in your country, you’ve been in exile for decades, it’s a horrible situation. Why aren’t you angry?” Now, can you imagine that being said to the leader of any oppressed people? They would have taken that kind of question, taken the ball and run with it: “Yes, there’s this and that. And these oppressors: these horrible people are doing this to us and that to us,” and on, and on, and on, and on, and on. And they would have just really spewed their anger out. His Holiness sat there and he said, “If I were angry, what benefit would it be?” He said, “There wouldn’t be any benefit. Even on a personal case: I wouldn’t even be able to eat properly I’d be so disturbed by my anger. I couldn’t sleep well at night. What use is anger?” And this interviewer, this reporter, just couldn’t believe it. But His Holiness was really speaking from the heart.

Audience: [follow-up question about pacifism and inactivity.] The world is so attached to this feeling of violence; and this attachment to violence itself would be a cause for them take a step back from helping people who are trying to do something in a non-violent way. So people are helping the Tibetans less because of their [the Tibetans’] non-violence.

VTC: I don’t know.

Audience: I think he [the Dalai Lama] uses this as a teaching tool.

VTC: I think he definitely uses this as a teaching too. And I think Tibet has invoked the sympathy of the world in many ways because they are non-violent. And would people help Tibetans more if they were taking hostages, and killing people? I don’t know. I don’t know. Maybe people would hate them more too.

[Audience responds about how our world is habituated to respond to violence with violence; so folks don’t know what to do]

VTC: Well, people are bringing political pressure on China. Would an armed uprising in China help the Tibetans? I don’t think so. I think it would cause them much much more suffering. There’s no way they would ever gain their independence from the Communist government by staging an uprising. The PLA (People’s Liberation Army) would come in there and just squish them. So I don’t think that would help them to gain their freedom in any sort of way at all.

Audience: I think this situation is teaching us as beings how to find creative ways to deal with conflict and violence without having to go in the way we have always gone. It’s taking us some time to figure out how to do that which is successful and beneficial and doesn’t entail imploding the place.

VTC: Right. His Holiness is putting that challenge to the world. Attachment vs. Love in Relationships Q: [Question about relationships: how to balance projections/attachment and reasonings/meditation.] You fall to seeing that relationships are nothing and I should move on. No! I would like to find a balance and I believe there must be.

[In response to audience] So you’re asking about a balance in a relationship between this whole thing of not superimposing happiness on what is dukkha by nature and what is clean on what is unclean; and yet still have a healthy relationship. So now I’m going to give an answer that’s directed towards lay people in relationships. His Holiness has often commented that really to have a good marriage, the less attachment you have the healthier your marriage is going to be. So the more you’re able to see other people more accurately, then you’re not going to be superimposing so much on them so you won’t have so many fanciful expectations that lead to a lot of disappointment. If you see your partner as another sentient being who’s under the influence of ignorance, anger, and attachment, then you have some genuine compassion for them. When they are out of sorts or they do something you don’t like, you can have compassion for them. Whereas if you ‘re attached to them and this image of how you want them to be, then when they don’t do what you want you get really upset. So in actual fact, reducing the attachment is going to lead you to have a healthier relationship. Instead of having what we call love, which is actually attachment, you’re going to have what is actually love, which is a wish for this person to have happiness and its causes. Because attachment is always linked to: I love you because you do da, da, da, da, da for me. And then of course when they don’t do it then you get mad. But love is just: I want you to be happy because you exist. So if you can have more of that feeling and less attachment in a relationship your relationship will be much healthier.

One last question and then we have to stop.

Audience: I’m having some difficulty in the group practice sessions while I’ve been here with incredible laxity of mind. Almost like holding a heavy beanbag over my head and wherever I push it up, whatever method I try, it just keeps covering me. And normally when I have that I’m by myself so I can get up and I can sweep the floor, clean the kitchen, do some physical activity and let my mind calm that way; because no matter what I try when I’m sitting it’s just not working.

VTC: So you’re falling asleep a lot?

Audience: No, I just can’t concentrate on anything.

VTC: Because you’re falling asleep or because you’re distracted?

Audience: Distracted. So I’m just wondering, within the setting of group practice and not being able to get up and make noise, is there anything I can do other than just keep persisting?

VTC:

Well, that’s kind of it. Because even you get up and start sweeping the floor that isn’t going to get rid of the distraction in your mind, is it? That’s just giving in to the urge to get up and do something else. So this thing of distraction; this is very natural and very typical. Everybody is going through it, it’s not just you. So everybody struggles with it.

There are a few things that I think can help. First of all, doing some prostrations, the 35 Buddha practice with the confession, before you sit down to meditate. I think that can be very helpful because just that already is purifying your mind and steering your mind in the right direction. Another thing that could be very helpful is doing some walking meditation before you sit. And when you do the walking meditation synchronize your breathing and your steps; not in a forced way but in a very natural way. And if you can do that then both the body and mind get much more tranquil. And then you go from your walking meditation just to sitting down. And then that tranquility is kind of there to start with. So you can try some of that.

So let’s sit quietly for a couple of minutes and then we’ll dedicate.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.