Taking retreat into daily life

Taking retreat into daily life

Part of a series of teachings given during the Manjushri Winter Retreat from December 2008 to March 2009 at Sravasti Abbey.

- Intergrating the retreat experience into daily life

- Questions and answers

- Why don’t you automatically go into compassion after you have a realization of emptiness?

- Developing concentration and mindfulness

- The bodhisattva path and the arhat path

- What is realizing the nature of your mind?

- Mind and mental factors

Manjushri Retreat 08: Q&A (download)

So this is the final talk about how to come out of retreat and how to integrate this with your life [given especially for those at the Abbey for just one of the three months of retreat]. So you had a very rich experience, as we heard in the afternoon go-around. When you leave, continue with what you have been doing here. In other words, don’t think, “Oh, I was just doing it here and now,” you know, for those of you who are leaving or those of you who are going to start offering service [not being in the meditation hall so much] this month. Don’t just think, “Well, okay, now I just drop everything I did in retreat. Now I kind of act my dysfunctional normal self.” But instead really think, “Well, I set up some good habits, and so now I want to keep those good habits going.” So make sure you meditate morning and evening. People at the Abbey do that kind of automatically, that’s the advantage of living in a community.

So just keep on with whatever good energy that you’ve been cultivating; and just keep on doing it. And when you go back, remember that your family and your friends and all had a different experience with last month. And so they not only want to hear about yours, but they want to tell you about theirs. So just be aware of this and don’t expect that because you had an unusual experience here, that they are going to see it as more important than the car breaking down, and the snow, and a problem at work that they experienced. Just realize that they are not at the same space you’re at. So don’t expect them to understand everything. What I generally advise is that if people are interested, you can talk about your experience, but do it in little bites at a time. And let them show their interest. Because sometimes there is the tendency of: I just want to tell everybody everything I’ve experienced. And maybe they don’t want to hear it. And maybe it’s not so good for us either. Because sometimes we start talking a lot about everything—then it’s just becomes an intellectual memory, instead of a treasured experience that we had.

Especially in your daily life, really keep up the good habits that you have set up here, in terms of getting up early, speaking less. Like I was saying the other day, in breaking silence, don’t go out and start chatting all the time, going to movies, and stuff like that. Because you may feel, “Oh, my mind is still very noisy.” But it’s a lot quieter than it was when you came. And so if you go out and put yourself in situations where there is music and entertainment and parties, you’ll find that you get quite exhausted. And all the energy you built up here will fizzle. Because there is energy in those kinds of social situations, isn’t there? I mean the energy of greed, or of distraction, or the energy of anger, whatever it is. So just be aware that you are kind of open and susceptible.

Sometimes when you are leaving a good situation for practice, like this has been, there’s a tendency to be a little bit sad, and to feel, “Oh, I’m going to lose everything,” and “Woe is me,” and “What am I going to do?” And, “Where is the support going to come from?” And, I find it much better, instead, to think, “I’ve just had this wonderful experience, and my heart is very full, and so now I’m going to take that fullness out and spread it to everybody that I encounter.” So instead of seeing this as: I’m losing something by leaving, see it as: I’m taking the Abbey and what I gained in my meditation practice with me, to wherever I’m going, and I’m going to spread that good energy to all those people there. Because good energy is not a fixed pie, if you give it away you are not going to run out of it. So really have that thing of: I’m going to share what I’ve learned here with the people that I encounter. Okay?

How to relate the practice to your life

And then how does this practice relate to your life? You probably have been spending a good deal of your time in the hall thinking about yourself. So, hopefully, you’ve been relating it to your life. “I’m practicing.” Because when we think about ourselves, it is all about me, I, my, mine. And so hopefully you have been developing some of the antidotes, some of the different perspectives to apply when those same old mental states come up. And so practice those antidotes when you go out. And a lot of people say, “I’m so jazzed up, going to my family, how would I tell them how wonderful it was and get them excited about the Dharma, just like I am excited about the Dharma, because they aren’t so excited? How do I get them excited?” And I always tell people to take out the trash. Because if you take out the trash (that’s figurative, but, you know, for some people it’s real). But just do something kind, that you usually let other people do for you. In other words extend yourself in kindness—to do something that you usually never do for others. And doing that will show to your family and friends more than any words, the value that the Dharma has had on you, the benefit it had on you. I always say, “You take out the trash.” And then mom goes, “Wow, 45 years I’ve been trying to get my son to take out the trash, and one month at that Buddhist retreat and wow, he took it out. I like Buddhism.” You know, it speaks very loudly.

We had one woman, when I was teaching in the Dharma Friendship Foundation in the early years, she had lupus, so she was in a wheelchair, and she also had red hair, and a temper. So they used to call her “hellfire on wheels” at work. She worked at the F.A.A.. And then she started practicing Dharma. And some of her colleagues noticed this change and would come in to her work space and say, “What’s happening?” And she ended up loaning the whole set of lamrim teachings that I gave, like 140 or 150 tapes, to one of her colleagues, who listened to all of them because he was so impressed with the change that he saw in her.

Questions and answers

Do you have any questions about ending the retreat or how to adapt?

The eight Mahayana precepts

Audience: Is it possible to take the eight precepts later, by the phone?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Oh, by the phone? Now the thing with the eight precepts is that if you have taken them before, from somebody who has them, then when you go home, you can take them on your own. But, are you saying that you have not taken them before and you want to take them for the first time? If you want to keep the eight Mahayana precepts on your own, and if you had that transmission, then you can just visualize the Buddha in front of you, do it in front of an altar. And then say the prayer as if you are saying it in front of the Buddha, and take the precepts that way. It’s very good to do that; and if you can do it on new and full moon days it’s very good, and whenever else you want to.

Audience: She does not have the transmission.

VTC: So she does not have the transmission. So, you are saying that you want to take them. I see. Okay. But you actually want to take them sometime from me, so we can do that over the phone sometime.

Distraction and tightness in meditation

Anything else? No more questions?

Audience: One of the things that distracts me in the meditation is about how to balance between not too tight and not too loose, it seems like I put in a lot of effort.

VTC: So, you are saying that meditation practice is a lot of effort. Well, it is. So, it depends on what kind of effort though, whether it’s joyous effort or pushing effort. They are different. So you are asking how we find a balance, so that we can relax and yet also extend ourselves in practice. I think this is really the difference between pushing effort and joyous effort. Because when there is pushing effort there is this attachment to it, so there is no relaxed mind in it. When there is joyous effort, then the mind is quite happy to be doing what it is doing. So then the trick is how to create a joyous mind. And I think that can be done by thinking of the benefits of the Dharma practice and thinking of the qualities of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Then we feel inspired by them and we want to develop these qualities ourselves, and so our mind becomes very joyous. Some times when we think of meditation as effort, especially with concentration, I’ve noticed that I do this: is I think, “Oh, I’ve got to concentrate.” What is our usual thing, when we were kids, and somebody said, “You have to concentrate.” Look at his face [face squinting, up tight], you know, it’s like, “Oh my gosh, concentrate!” So I tighten my body, I tighten my mind, I close my fists. You know that kind of thing is going to make you have more distraction in your meditation. Because when you tighten too much, it causes agitation, it causes excitement in the body, it makes your body-mind too tight. It’s going to cause more distraction. So then you say, “But if I relax, then I’m just going in the direction of my laziness, and I’m never going to make any improvement.”

Exploring a relaxed mind

Do some exploration in your meditation about this—what you understand as relaxed and what you understand as effort, and what you understand as concentration. Because we usually think of relaxed as not making any effort and letting whatever comes in the mind to come in the mind. But when we do that, is the mind actually relaxed? Or when we let come in the mind whatever comes, does the mind goes into anxiety? Does it go into worry? Does it go into greed and attachment? Does it go into complaining? Does it go into anger? Does it go into spacing out? And is the mind really relaxed when we just let anything come in to it? Because whenever we hear the word “relax,” that’s what we think: “Just don’t think anything. You have no control over your mind. Just let it be.” But then we find that actually we are not very relaxed when we are trying to relax. Have you ever noticed that? So what we do to relax often does not make us relaxed. It makes us tighter, because some times what we do to relax then we criticize ourselves for later. The we feel worse about it later on—instead of more relaxed.

So I think we have to do a little bit of research about what relax means. Because when you are trying to develop some concentration in your meditation, your mind has to have a certain degree of relaxation. But relaxation doesn’t mean lack of mindfulness. And relaxation doesn’t mean lack of sampajanna, this untranslatable mental factor of clear comprehension or introspective alertness. Relax doesn’t mean that you have a lack of those things. Because this is the thing, when we hear the term introspective alertness, so what does that conjure in the mind? “Oh, I have to be alert!” Okay? Immediately we’re tense, aren’t we? Introspective alertness, so that isn’t that mental factor. So there has to be a tone of relaxation for that kind of alertness and clear comprehension—that understands what we’re doing and that is aware of what’s going on in our mind. For that to arise there has to be some space. And tightening, and equating effort with tightening, is a big mistake. I used to think that when I had distraction, let me get this right, well, I won’t say it, because I don’t have it right in my mind. But I used to apply the antidotes incorrectly, put it that way.

Losing concentration, following the breath, being receptive

Audience: Since you’re talking about this, I’ve been experiencing losing concentration off and on. There’s the experience of you’re getting off your object and in order to stay on it you experience that you should apply more effort. You think you should try harder to force it back where it’s supposed to go. But the reason it’s going off is because you’re already so tight.

VTC: Exactly.

Audience: And then, you know I’m doing the opposite, which is: I’m more steady on the object, like you said just getting these two things confused. But I thought it helpful, I read in a book maybe by Pabongka Rinpoche, and he said, “My mind is too tight and so I relax it and immediately laxity arises. So I bring up some energy and instantly I’m excited.” The last line is something like, “How is one ever to achieve concentration?” It’s interesting how it jumps back and forth. And when I feel I’m doing it properly it’s kind of like how you said that the middle way isn’t halfway between the two extremes, but it’s more like the third way. It’s the one that’s neither of those two. It’s not like cut them in half and stick them together.

VTC: Right.

Audience: It’s not like too loose, too tight. It’s like, when you find the right spot, you’re simply not one string that’s in tune. But my actual question was that when I find that I’m starting to focus more, it seems that I am more subjectively aware than objectively aware, and I wonder whether or not that is the correct approach?

VTC: What do you mean subjectively aware vs. objectively aware?

Audience: Simply watch your breath as one of the objects of meditation. When I watch my breath, like I try to watch the object of my breath, it’s seems like I’m automatically either excited or relaxed. And as soon as I try to correct one I swing. But when I try to watch the experience of breathing it’s a whole different thing. And sometimes like, just recently I was just experimenting just being aware, like kind of trying to bring to mind the title of the book, Be Here Now, that I’ve never read, but just this sense, of this subjective sense; and the experiential sense of being aware. I don’t know if that is correct or not.

VTC: If you’re thinking of your breath as something out there, that you are focusing on…

Audience: I’m in my body but it still seems objective. It seems out there.

VTC: You want it to be very much experiential. And it’s good to keep your focus here, on the upper lip and the nostrils, if you can. And, just be aware of the sensation as its passing. But it’s definitely your sensation of the breath as it’s going there. There has to be some kind of relaxation in there. Because sometimes there is the tendency to visualize yourself breathing, you know, so, you’re visualizing yourself breathing. Or you’re visualizing the air going in and going down, and visualizing it coming out. No, no, you just want to focus here [at the nostrils/upper lip] and watch. It’s very helpful in the The Mindfulness of Breathing Sutra they talk about when you’re breathing in long, to be aware that you’re breathing in long; when you’re breathing out short, to be aware that you’re breathing out short. When you have some awareness of how your breath correlates with your different emotions and mental experiences, then you can start tranquilizing your whole body—by how you are breathing and being aware, in that way.

It’s very interesting that in the Satipattana Sutra, The Mindfulness of Breathing Sutra, actually it all grafts onto the four establishments of mindfulness. Because in The Mindfulness of Breathing Sutra has sixteen steps, and they have four steps for each of the four types of mindfulness—mindfulness of body, mindfulness of feelings, mindfulness of mind, and mindfulness of phenomena. So it’s quite interesting how they kind of go together. And similarly some people are, let’s say, using the object of the Buddha, as what you’re concentrating on, and there is a tendency to visualize him [with her eyebrows squinted tight]. You do this [indicating a person in the room]. When you sit to meditate, and as soon as you sit down even here in the room: eyebrows narrow. So just be aware of it. Because it’s like, “Oh, I’ve got to concentrate.” Or, “Oh, I’ve got to see the Buddha.” And so, all of us do this. She just happens to close her eyes and so we see it. The rest of us do it when we’re in there [the meditation hall], so not everyone sees it. But then what happens is that there’s some tension there, instead of what we want to have—a receptive state of mind—to be receptive. So in our normal life we’re always active and we’ve got to get something. So here in our meditation, we do have to do things, and think about different things, and so on. But we have to create some attitude of receptivity in our mind, instead of always, “Striving to get this!” and, “Striving to get that!”

Audience: I keep thinking no resistance. That works really well for me.

VTC: Yes. That’s very good, yes, no resistance.

Arhats and compassion

Audience: This actually was inspired by C’s question, a couple of weeks ago I was thinking about people who reached the state of nirvana. So they realized emptiness directly? So then all the ignorance has been cut?

VTC: Yes.

Audience: So my question is then, if you’re in that state, and you have Buddha nature, it just strikes me as odd that you wouldn’t automatically have bodhicitta—because all that negativity isn’t there and Buddha nature is exposed, so?

VTC: So why don’t you automatically go into compassion when you [realize emptiness]? I think it depends on people’s previous training. If people have a lot of training and compassion beforehand, then when they realize emptiness, then they have compassion for everybody else who doesn’t realize it. And they don’t have the limitations of their own anger and attachment and so on. And so some people might be able to go into compassion. But if you’ve had this mind of, “My liberation, my liberation, my liberation,” then when you have your liberation you’re not necessarily going to start thinking, “Well, I want to go back and accumulate merit for three countless great eons so I can benefit sentient beings.”

Audience: Well, that’s interesting because it still seems like then they have a definite limitation, like a negative?

VTC: It’s not this gross kind of attachment and everything that we have, but there are some obscurations still left on the mind: of preferring one’s own nirvana to others’ nirvana. Or so they say, I have no experience of it—all these things between Buddhas and arhats, and all that. But I did see when I was in Thailand, that it makes me see that maybe what you do early on in the path sets up different habitual tendencies that direct your mind later. And so, I would hear somebody tell a story, and it’s just like, “I knew somebody who just wanted to get liberated. And they figured that was the best way to do it. And they just were going for that. And they weren’t interested in having to do so many virtuous actions to create all that merit, to be able to fully cleanse the mind. They just wanted to get out of samsara.”

Audience: It seems like it would also depend a lot on not just your attitude in this life but what you came into this rebirth with. Some people seem to have, you know, a tremendous sense of compassion from when they’re [young].

Cultivating compassion and bodhicitta

VTC: Yes, and then there are the rest of us that have to really train our mind to be compassionate. But what she’s saying is that when you reach nirvana, you don’t have the impairments of ignorance, anger and attachment. So why doesn’t compassion spontaneously arise in the mind at that point? And so I was saying, if you look, in Nagarjuna’s Essay on Enlightenment, he talks there, first about ultimate bodhicitta, and then about conventional bodhicitta—as if you realize emptiness and then you go on into great compassion in your practice. But I think to do that—because I heard His Holiness say that you have to cultivate compassion separately. But to me it seems like for that approach, where you first realize emptiness, and then have compassion; so that you stay in the Mahayana path with that—that you have to have had some tendency towards compassion to start with. So that your mind steers in that direction when you have that realization of emptiness; and that you’re willing to do the work for three countless great eons. Some people may say, “Too long! I’ll be compassionate while I’m alive and I’ll help people when I’m alive …”

But there’s a big difference between being compassionate and having bodhicitta. There’s a big difference. So, arhats are definitely compassionate. Sometimes the way you hear people talk about them you get the feeling like they’re so selfish. They’re not. They are very compassionate. They’re much more compassionate then we are. But there is a difference between having compassion and bodhicitta.

So, think about that.

That’s why I think it’s important: just this imprint of bodhicitta again, and again, and again, and again, and again. Because at a certain point you could think, “Wow, I’m getting somewhere in my practice. Three countless great eons? Okay, I don’t have any anger for those idiots any more, [laughter] but three countless great eons? You know, I just want my own peaceful nirvana.”

Audience: I like to think that two-and-nine-tenth countless great eons are behind me; that somebody else did all that work already. [laughter]

VTC: No, it’s actually the three start when you enter the path of accumulation, which, I don’t know about you, but I haven’t entered the path of accumulation so my three countless haven’t even started.

Audience: So I should let go of that fantasy. [laughter]

VTC: So this is why you have to develop a very strong mind, to do that.

Audience: Venerable, I back on D’s question. Because if you actually understood emptiness, then you’ve understood the emptiness of the “I”; and so then why would you prefer “your own”—the emptiness of that being—over anyone else? There is no being to put ahead of others.

VTC: It’s not like arhats are going around saying, “I’m liberated, and I don’t care beans about you, go to hell.” I mean arhats are not talking about that. But it’s just like, “There is no “I” there and other people have no “I”, so they’re are equal—so why should I extend myself?”

Audience: Oh, but I would see it the opposite, “So they’re equal so why wouldn’t you?”

VTC: Yes, you see, that’s if you’re practicing bodhicitta. You train your mind to think that way, “We’re equal so why shouldn’t I extend myself?” But our normal mind, if we don’t think that way, it’s, “We’re all equal. Why should I?”

The nature of the mind

Audience: So what they refer in the different traditions to realizing the nature of one’s mind, is that referring to achieving nirvana or achieving Buddhahood?

VTC: Well, realizing the nature of your mind? It can be done on either path. And it’s a realization prior to either nirvana or Buddhahood.

Audience: Is it different from realization of emptiness?

Audience: Because the nature of the mind is emptiness so they should be equal.

VTC: Right.

Audience: So they should be the same.

VTC: Right.

Audience: Because sometime the semantics …

VTC: Well I think the thing about realizing the nature of the mind—or the emptiness of the mind—why the mind in specific is so important, is because usually when we think “I”, that “I” is associated with mind. So when you realize that the mind has no true existence, then you’re really undercutting both the grasping at self of phenomena and grasping at self of person.

Audience: I was thinking at one point because we had these mind and mental factors, there are the five omnipresent mental factors which should be present in a Buddha’s mind because he should be aware of the discrimination, attention, and so on. It would seem, so that’s not empty, there is something there.

VTC: But those are mental factors that are all focused on the object emptiness. Emptiness doesn’t mean that there’s no mind. Emptiness, we’re talking about the ultimate nature, the mode of existence, that they are empty of, of inherent existence. So the mind that realizes that emptiness of inherent existence: that mind—the cognizing mind that’s the subject realizing that—has mental factors. But there is no sense of a subject that’s realizing the object emptiness when there is the nondual realization. So they say, I have no experience, but that’s what they say.

Karma

Audience: I just wanted to thank you for all the teachings on karma because I’ve always kind of pondered, “How could I have all of this really bad stuff [happening] at the same time that I have good stuff. Somewhere I had some kind of misconception that it should be either/or. And I can see now why.

VTC: Because we have all different sorts of karmic seeds in the mind stream and different ones ripen at different times, so our lives are quite a mixture of happiness and pain.

Audience: It’s been very helpful.

VTC: Good. Good.

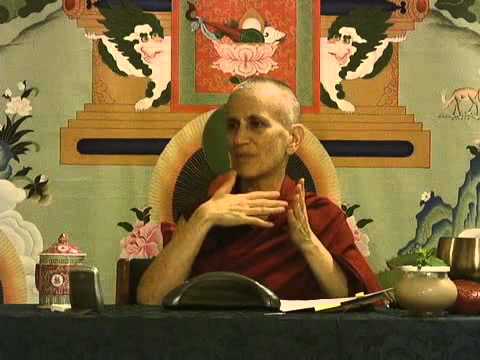

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.