Living as a Western monastic

Living as a Western monastic

Kalayanamitra, an organization that supports Western and other non-Himalayan monastics practicing in the Tibetan tradition, asked Venerable Thubten Chodron for an article for their newsletter. She wrote about her experiences in becoming a Buddhist nun.

“You’re becoming a what?” is the response that most of us Westerners who have become Buddhist monastics received upon telling our family and friends of our decision to ordain. In Asia, becoming a monastic is a respected and accepted “career choice,” but in the West, people often think we’ve lost it. “You’re going to be celibate?” they query, “Are you nuts?”

If someone had told me when I was 21 that I’d be celibate and a monastic, I would have told them they were nuts! But five years later, there I was taking lifelong vows as a Buddhist nun. Thirty years later, I look back and see that that was the best decision I made in my life. Everything I’ve been able to accomplish, whatever I’ve been able to do to benefit others, and the small steps I’ve taken towards liberation and enlightenment have all been done on the foundation and with the support of living within monastic precepts. That’s not saying that everyone should ordain—this is a personal decision that is not good for everyone—but for me it was an excellent choice. People ask me if I’ve ever regretted it. No, I haven’t. If I had, I wouldn’t have continued. They ask me if it’s been difficult. Yes, sometimes it has been, but the biggest difficulties I’ve faced have been due to my ignorance, attachment, and animosity; it’s not precepts or monastic robes that cause hardship.

As one of the first generation of Western monastics in the Tibetan tradition, I’ve encountered a variety of external difficulties, such as visa and health problems when staying in Asia, lack of financial and moral support when living in the West. But I see these problems as part of the path and tried to apply the Dharma methods to calm the mind that would get worried about them. But for me, the benefits of being a monastic have far outweighed the difficulties because the precepts are an excellent structure within which to train the “monkey mind.” They guide the mind to give up its trips; they lead us on the path of compassion for ourselves and others. Living in precepts is part of the Higher Training of Ethical Conduct, which lays the foundation for the Higher Trainings in Concentration and in Wisdom. Our teacher, the Buddha, was a monastic and wearing the robes reminds me that my aim in life is to emulate his mental, verbal, and physical activities.

Tibetans grow up with Buddhism and monastics. They know what the life of a monastic entails and when they ordain, they are welcomed into a monastery where they live with monastic relatives and others who are from the same area of Tibet as they are. While Tibetan monastics in general are not rich, the senior monastics take care of the juniors, providing them with room, board, and teachings, and together they share the experience of living in community.

The situation for Western monastics is considerably different. There are very few monasteries where they can stay in the West. They may live in a Dharma center, in which case they often spend long hours doing volunteer work building the center or planning activities for the lay people. They usually do not receive special training as monastics because the Dharma centers are designed principally for lay people. Tibetan monastics are sponsored at Dharma centers and receive offerings and stipends, most of which they send to support their disciples in India and Tibet. However, many Western monastics have to work at jobs in the city in order to support themselves as some Dharma centers ask the monastics to pay in addition to volunteering their services. They do not have time to study and practice the Dharma, which inhibits their ability to serve the lay people by teaching and setting a good example. Keeping their vows is very difficult for those who must work in the city, and many do not survive as monastics.

While living as a monastic is wonderful, candidates need to be properly prepared before ordaining. They should first form a mentor-disciple relationship with a teacher who will train them as monastics and request that teacher for ordination. They should arrange to live at a monastery or a Dharma center with other monastics and have savings or monthly support so that they can live a monastic lifestyle without having to work in the city. It is also good training to live in the eight precepts for a year before taking monastic ordination. The booklet, Preparing for Ordination, gives other guidelines and points to contemplate for those considering ordination.

The Buddha said that his Dharma flourishes in an area where the four-fold assembly is present. These four are fully ordained women and men and female and male lay followers. Traditionally, the monastic community has been charged with preserving the teachings and passing them down to future generations. They have followed the example of the Buddha, living a simple lifestyle with few needs, devoting their lives to study, practice, and teaching others. For the Dharma to flourish in the West, the existence of the monastic sangha is essential. But for an indigenous monastic sangha to exist in a country, there must exist not only those who wish to ordain, but also those who wish to support them.

The Buddha set up the relationship of monastic and lay followers so that they are mutually dependent on each other and mutually care for and benefit each other. The monastics study, train, meditate, and practice the Dharma. The lay followers do these too, to the extent that their busy family and work lives allow. While monastics specialize in teaching the Dharma and counseling others according to the Dharma, lay followers share their material resources with the monastics, joyfully knowing that they are contributing to monastics’ ability to practice and become teachers. When everyone in this interdependent relationship practices humility, kindness, and service, this system works well. When they are arrogant, miserly, or disrespectful of each other, the adverse result affects them individually and as groups.

In late 2003, I began Sravasti Abbey in an attempt to provide a place where Western monastics could live and train and where those considering ordination could prepare for monastic life. The Abbey functions completely on dana, or offerings, and does not charge either lay people or monastics. We wish to make our life one of service that is offered freely and hope that others will support us in return. This involves a certain leap of faith that many people are not ready to make, but those who are find the discipline helpful for their Dharma practice. As examples of how we continuously cultivate a monastic motivation, I’d like to share with you some verses that we recite. At the conclusion of morning meditation, which is done as a group, everyone recites the following to reinforce their motivation of offering service:

We are grateful for the opportunity to offer service to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha and to sentient beings. While working, differences in ideas, preferences, and ways of doing things from our companions may arise. These are natural and are a source of creative exchange; our minds don’t need to make them into conflicts. We will endeavor to listen deeply and communicate wisely and kindly as we work together for our common goal. By using our body and speech to support the values we deeply believe in—generosity, kindness, ethical discipline, love, and compassion—we will create great positive potential which we dedicate for the enlightenment of all beings.

We eat only the food that is offered to us. When visitors bring groceries, they put their offerings in an alms bowl and recite this verse for offering food to the sangha:

With a mind that takes delight in giving, I offer these requisites to the Sangha and the community. Through my offering, may they have the food they need to sustain their Dharma practice. They are genuine Dharma friends who encourage, support and inspire me along the path. May they become realized practitioners and skilled teachers who will guide us on the path. I rejoice at creating great positive potential by offering to those intent on virtue and dedicate this for the enlightenment of all sentient beings. Through my generosity, may we all have conducive circumstances to develop heartfelt love, compassion, and altruism for each other and to realize the ultimate nature of reality.

The monastics respond:

Your generosity is inspiring and we are humbled by your faith in the Three Jewels. We will endeavor to keep our precepts as best as we can, to live simply, to cultivate equanimity, love, compassion, and joy, and to realize the ultimate nature so that we can repay your kindness in sustaining our lives. Although we are not perfect, we will do our best to be worthy of your offering. Together, we will create peace in a chaotic world.

Tears come to the eyes of both laity and sangha while offering food during this simple exchange. To me, this is a sign that our minds—as donors and as receivers—are being transformed into the Dharma.

May a strong, virtuous monastic sangha thrive in the West and all over the world!

June, 2007

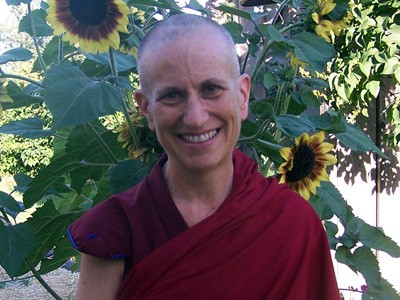

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.