The four messengers

The four messengers

Report on the 6th Annual Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering, held at Shasta Abbey in Mount Shasta, California, October 20-23, 2000.

Reverend Master Eko Little and the monks at Shasta Abbey hosted the 6th conference of Western Buddhist monastics for the third consecutive time. It took place from Friday, October 20 to Monday, October 23, 2000 in Mt. Shasta, California. This was the largest gathering ever with greater diversity and there was representation from the Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, Tibetan and Vietnamese traditions. There were four abbots among the 26 participants. Some persons had been ordained well over two decades and the newest monastic was ordained just months ago. The conference theme was “The Four Messengers”; the sights Prince Siddhartha saw when he explored the world outside the palace gates; revealing the signs of aging, sickness, death and the spiritual seeker. We used this as a presentation focus in our life as monastics.

Most guests arrived at the Abbey on Friday evening to the welcome introduction and opening by Rev. Master Eko, Abbot of Shasta Abbey (Japanese Soto Zen tradition) and Ajahn Pasanno, co-Abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery (Thai tradition). Everyone was invited to attend the evening vespers service and meditation with the resident monastics. And in the early mornings, many attended the morning services and meditation in the Meditation and Ceremony Halls. The services at Shasta Abbey are sung in English, set to Western Gregorian chant melodic style by the late Reverend Master Jiyu-Kennett who established Shasta Abbey in 1970. The services are uniquely beautiful and many participants looked forward to returning to the Abbey for these services.

Saturday morning, the first gathering was on the topic of “Aging” and Rev. Daishin from Shasta Abbey (Japanese Soto Zen tradition) presented his experiences of being in the monastery most of his adult life. He spoke of growing up and aging in the monastery as he has been ordained for twenty-six years. He started his talk by relating a recent visit to the local bank where he noticed that no one had gray hair. Was it that everyone was young or just appearing young? In our American society we deny and defy old age. We are a culture addicted to youthful appearance. Surgically and cosmetically we try to sustain youth and push away the reality of age in the hopes of remaining youthful. Living in a monastery, we don’t have to be compelled to engage in our life and aging in this way. He spoke of enjoying being older and of the satisfaction of monastic life. Discussion focused on how the natural process of aging is accepted and appreciated more as we deepen our practice and study of the Dharma. Reflection and blessing were held at the beginning and end of every session offered by monastics from different traditions.

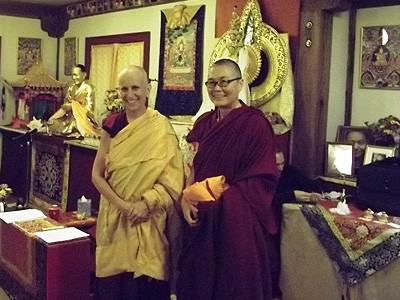

Ven. Karma Lekshe Tsomo (Tibetan tradition), assistant professor of Theology and Religious Studies at the University of San Diego, spoke on the topic of “Sickness.” She related her personal experiences with sickness while pursuing her Dharma studies in India and other countries. Some years ago in India, while viewing land sites for a nunnery, Ven. Lekshe was bitten by a poisonous viper. She spoke graphically about her three-month hospital ordeal in India and Mexico, and the difficulties that even seasoned practitioners may experience when confronted by intense pain and the uncertainties of serious illness. She described the traditional Tibetan explanation of illness and its causes, and presented a variety of Buddhist practices that can be helpful for transforming our attitudes toward illness, coping with pain, and using the experience of illness as an opportunity for practice.

On Sunday morning, two participants shared the topic of “Death.” Rev. Kusala (Vietnamese Zen tradition) spoke on the recent passing of his teacher, the late Ven. Dr. Havanpola Ratanasara, eminent master and scholar from Sri Lanka. The late venerable monk had founded the American Buddhist Congress, the Buddhist Sangha Council of Southern California, and numerous other organizations and schools in the United States and Sri Lanka. He spoke of the incredible teaching Dr. Ratanasara showed through his acceptance of approaching death and in mindfully releasing his responsibilities, turning away from this life and looking in the direction of his rebirth. Rev. Kusala said of Dr. Ratanasara, “He taught me the need to turn away from everything in this lifetime as death approaches and make ready for the next. ‘Don’t be attached,’ he would say; ‘It only leads to more suffering.'” Rev. Kusala also addressed the theme of dealing with grief as monastics.

I, Tenzin Kacho (Tibetan tradition), spoke on a different aspect of “Death” in the “Death of the Monastic.” I prefaced my talk saying that the focus was on the difficulties and concerns of Western monastics today and presented some of the encounters and views of lay Buddhists and lay Dharma teachers toward monastics. Some persons view monasticism as an austere self-centered practice and monastics as escapists not able to cope in society. Also mentioned were the comments of the head of a national Buddhist organization (name was not mentioned) who feels that there are only two jewels left in Buddhism anymore; that the Sangha has degenerated in Asia and is not accepted in the West. Some persons comment that there is no need for a monastic Sangha. I also noted that there were no monastic presenters at the “3rd Annual Buddhism in America Conference” held in October 2000 in Colorado. These views stimulated some fruitful discussion. In general, although concerned, the participants were optimistic and felt that we need to continue our efforts to study, practice and conduct ourselves well. With time, as we foster Dharma friendships with lay people and participate in Buddhist gatherings, the presence and value of monastics will naturally come to be recognized in this country. Excellent training and continued guidance is key before one takes ordination and especially in the early years of one’s life as a monastic.

Ven. Heng Sure, Director of the Berkeley Buddhist Monastery, a branch of the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas (Chinese Chan tradition) spoke on the Samana, the spiritual seeker and started by having each person share the signs or triggers that set each of us on to become monastics. This gave people a chance to express themselves and it was skillful, for it allowed everyone an opportunity to speak. He then presented ways of according with the Dharma and of the signs and form of the Samana. The evening before he had translated the “Poem in Praise of the Sangha” by Qing Dynasty Emperor Shunzhi (mid-17th century) and read it to us. He shared how the internal signs of the Samana were the combination of blessings and wisdom; that blessings without wisdom was like an elephant with a necklace and wisdom without blessings was like an Arhat (one who has attained liberation) with an empty bowl. Blessings come from making others happy.

Monday morning Sister Jitindriya from Abhayagiri Monastery (Thai tradition) presented “the Spiritual Friend.” She began her talk with the view that the Four Messengers can be seen as opportunities for awakening; that we don’t usually see them that way, but instead we see them as things to avoid. Because we don’t see suffering (dukkha) as an opportunity to awaken, as a ‘sign’ pointing out the truth of the way things are, we continue to wander aimlessly in samsara. Dukkha is a sign that can lead to liberation if we don’t despair. She suggested that if the Buddha had not awakened to dukkha in seeing the earlier signs, he might not have ‘seen’ the Samana, the sign of the renunciate would not have meant much to him. She quoted from many sources in the Pali suttas. As worldly beings we are intoxicated with youth, health, beauty and life, we don’t see their impermanent and unstable nature. The monk Ratthapala was asked, “Why have you gone forth when you have not suffered the four kinds of loss?” that is, of health, youth, wealth, and family. He replied in the manner of a teaching he had heard from the Buddha: that life is unstable and there is no shelter or protection in any world. Ananda, the Buddha’s attendant, said that association with good friends (those who encourage and help us on the Path) constituted half of the holy life, and the Buddha commented that the whole of holy life is association with good friends. Good friendship is the forerunner and necessitates arising of the Noble Eight-Fold Path.

Every session was purposely created with sufficient time for discussion after the presentations to allow questions, concerns, and dialogue in depth. It was encouraging to voice and listen to others’ personal views. Most of us have very busy lives alone or in monasteries and it is a true joy to spend some time in engaging conversations and learning about other monastics’ lives. Our gathering truly felt like a conference for and by monastics. Often topics of discussion at Buddhist gatherings focus more on particular interests and concerns of laypersons and lay teachers; the purpose of this conference is to meet and share monastic concerns and to enjoy the company of others who have gone forth. This fundamentally different orientation highlights the importance of holding monastic conferences as much as possible at monasteries. The purity of the Sangharama (monastery), this time the hospitality we enjoyed at Shasta Abbey, lends a priceless support to our gathering.

The participants expressed deep appreciation for the rewards of the 6th Monastic Conference. Our time together was brief, but precious, as the program brings together studies, traditions, inspiration and wisdom from America’s diverse Buddhist cultural traditions. The very fact of our gathering with six monastic traditions testifies to the gradual deepening of the Dharma roots in Western soil. The historic significance of our gathering, the community we create, and the merit and virtue generated when the Buddha’s Sangha gathers in harmony is truly an occasion for rejoicing!

We have set the dates for the 7th Western Monastic Conference for October 19-22, 2001, with the theme tentatively set for “Monastic Ordination and Training.” We encourage other western Buddhist monastics to join us next year and thank the American Buddhist Congress for offering some financial assistance for travel to this 6th conference.

Tenzin Kiyosaki

Tenzin Kacho, born Barbara Emi Kiyosaki, was born on June 11, 1948. She grew up in Hawaii with her parents, Ralph and Marjorie and her 3 siblings, Robert, Jon and Beth. Her brother Robert is the author of Rich Dad Poor Dad. During the Vietnam era, while Robert took the path of war, Emi, as she is known in her family, started her path of peace. She attended the University of Hawaii, and then began raising her daughter Erika. Emi wanted to deepen her studies and practice Tibetan Buddhism, so she became a Buddhist nun when Erika was sixteen. She was ordained by His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1985. She is now known by her ordination name, Bhikshuni Tenzin Kacho. For six years, Tenzin was the Buddhist Chaplain at the US Air Force Academy and has an MA in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan Language from Naropa University. She is a visiting teacher at Thubten Shedrup Ling in Colorado Springs and Thubeten Dhargye Ling in Long Beach, and a hospice chaplain at Torrance Memorial Medical Center Home Health and Hospice. She occasionally resides at Geden Choling Nunnery in Northern India. (Source: Facebook)