Practicing with a year of illness

Practicing with a year of illness

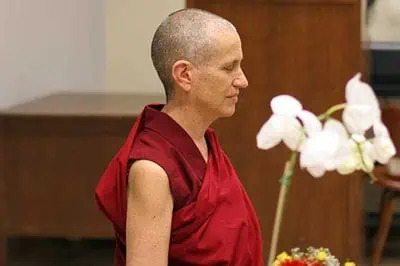

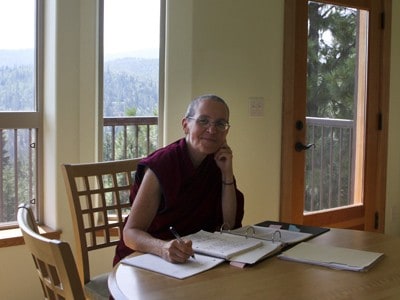

Venerable Thubten Semkye reflects on how a prolonged illness provided an opportunity to examine deeply held concepts about herself, and apply the Dharma teachings.

This year, 2009, has become more important in regards to my Dharma practice than perhaps any year so far. For someone who has had the good fortune to have a healthy body most of her life, this past year of illness has shaken something very deep within the core of my being. My identity is strongly aligned with the state of my bodily strength, agility, and endurance, and it’s been crumbling since February when I was diagnosed with bronchitis and fatigue. In July after a routine colonoscopy, a bowel obstruction was found which required a nine-day hospital stay followed by some superficial blood clots that occurred from lying down for those nine days.

The anxiety that kept arising with these illnesses this year was pervasive and persistent. The questions of “Who am I if I am not strong and healthy? What am I worth? Who will love me? How will I earn my keep at the Abbey?” kept my mind full of fear and worry. My sense of who I am is tied up in the roles I have at the Abbey, the tasks and projects I facilitate, and my capacity to participate and implement them. With these illnesses, all of those identities have been challenged and shaken, and in some way left to crumble and fall apart.

Another terrifying experience was in regards to the biggest lie uncovered through it all—that I was totally in control of my body, my health, and my life. What an eye-opening revelation it has been to realize that this is a major misconception that I have assumed to be true all my life. In fact, most of the time I have minimal control at best in regards to what happens to my body, my mind, the world and people around me.

Am I my body?

The body is a great tool for seeing this, especially when it’s not feeling well and its parts are not functioning as they are meant to. And it changes moment by moment. There is nothing solid about it! Because I am so identified with my body, I kept trying to hold it all together through the pain, the tiredness, the weakness, and the IVs because this is “Me!” But it kept changing and falling apart more and more! At times I was able to ask myself the question, “Semkye, are you sure you’re this body? If you are, where are you, what part of this body are you?”

I would feel the sensation of the lungs or the colon or the veins in my legs and say, “Are you your lungs? Are you your colon?” This got to be a pretty big question because my sense of “I” is definitely sensed in the front of my chest in the lungs and stomach area. I hold my breath a lot, and I sometimes find my stomach in knots when I get anxious. (Funny how the bowel obstruction was literally a knot in the intestines!) When I could honestly sit with these questions as the days went by in the hospital I would hear a quiet yet clear, “No!” to these questions. Then even for a short time I was able to be with what was happening to my body—yet not identify myself as my body—in an open-hearted attentive way and not feel threatened.

Am I my mind?

When I found myself afraid or irritated or weaving novels in my mind, I also began asking myself, “Are you this mind? What part of the mind are you? Are you the fearful mind, the compassionate mind, the anxious mind, the mind that tells itself stories, the mind that notices the light in the room?” And for a flicker of a moment I could see clearly that I was not any part of those minds. It was fascinating to just watch my mind go all over the place and shift into different states at a moment’s notice—not owning them or identifying with them, but just watching to see how fleeting and unfounded they were.

Another aspect of Semkye I got to look at was her dissatisfied mind, which was never happy about any of the illnesses or the circumstances surrounding them. It would gripe and whine, be bored, and run away to anything that would keep me from being with the present situation. I began to see a deeper truth: that running from my life is the major cause of all my suffering and an act of abandoning myself. Not the sickness, not the pain, not the weakness but the running away.

From this awareness an honest, and deep question emerged. “So Semkye, what’s it like to be in the present moment and not abandon yourself?” At first, I found staying in the present boring. There’s no storyline, no drama where I’m the main star, no inner commentary about everyone else that I believe to be objective and truly existent. I became keenly aware of a constant fight going on inside—wanting myself, others, the situation to be different than they were. It was really exhausting. I began to put the pieces together that showed me that perhaps this exhaustion from fighting the truth of my situation was one of the main reasons for my illnesses.

Stop fighting with the world

At some point my wisdom mind finally broke free, stepped in and said, “Enough! Give it up!” As the weeks turned into months, this wisdom mind would bring me back to myself over and over again, and I could feel my body relax and my breath slow down. In those rare moments where I could notice, I began to feel this space inside my mind that was healthy, uncomplicated, and fresh.

What is this fighting with the world and myself all about anyway? Everything is impermanent by its very nature, changing moment by moment. That truth makes me so uncomfortable. But no matter how hard I try to fight, manipulate, cajole, negotiate, kick and scream, state my position, hide away, none of my efforts change this fundamental truth.

It sometimes appears that I am always jumping off of cliffs (or more likely being pushed) as life surprises and shocks me when I try to control things. As Venerable Thubten Chodron has said, our lives are not about jumping off of cliffs. That analogy assumes we have some solid ground from which we jump. But we don’t even have that. All our afflictions, the eight worldly concerns, our opinions, our ideas, our self-centered thoughts are all our unending exhaustive efforts to try to find some solid, permanent ground to stand on in this impermanent, transitory world. But, as I am starting to see over and over again, the fantasy of solid ground lasts maybe a minute at best. And then it’s gone.

Living with impermanence

Lying in a hospital bed for nine days just watching my body and all the thoughts my mind had about what was going on with my body was enlightening. I kept being blown away by the raw fact that I didn’t have any idea what was going on or what was going to happen in the next moment. At times I could hold that thought with not much of a struggle. At other times, especially when one of the nurses or doctors would say, “This is going to hurt a bit,” or, “This is going to be uncomfortable for awhile,” I would get so tight and scared. I saw my grasping to control that which I had no control over as the source of my misery.

So how do I live my life with its impermanence, its surprises, this groundlessness in a way that deepens my understanding of the Dharma rather than adds to any current need to fix or control or scramble for ground? The best I can do is to cultivate a basic friendliness and loving-kindness towards myself. I continually return to the present, to my life without a story, without control over its unfolding with a sense of curiosity and willingness as well as I am able.

The question then arises: What does it actually mean to be a friend to myself? What qualities do I try to express in my friendships with others? I want to be trustworthy, kind, open-hearted, to accept differences, curious, have a sense of humor, honest, and compassionate to name a few.

Being my own best friend

Of these, which ones do I generate in relation to myself? This was hard to look at, but I had to admit that at this present time, I have honesty, some compassion, some tolerance, and encouragement, but not much else. Why is that? Why is friendship to myself so hard to generate? This took some thinking, because I have this belief that I’m a good friend with myself already, so I rarely feel the need to check in to see how this friend is doing—”I know her so well … She’s fine.” Another insight I had into this question is I am far too busy looking for approval outside myself. And lastly and most important is that I have deep within me the misconception that I’m flawed at some basic level and really not worth the time. Perhaps it’s time to re-evaluate this friendship with myself for the long term goal of peace.

As I slowly recover within the supportive, loving environment of the Abbey community, I am given a rare opportunity to rest and ponder the deeper insights that have emerged from these illnesses this past year. Within my present environment of quiet and calm, I am attempting to return to the present, time and time again, in order to familiarize myself with the sensation of it in my body and mind in preparation for my return to daily community life with its busyness and level of engagement. I aspire to make this my core practice for a long time to come—to embrace rather than fight whatever shows up, to be relaxed in the groundlessness of this impermanent ever-changing world, and to befriend myself and, by extension, all I meet. I aspire to be able to be curious rather than defensive, flexible rather than hard-headed, and appreciative of others’ differences rather than disappointed.

I will always remember the incredible kindness of my caregivers at both Newport Community Hospital and Sacred Heart Hospital. Their concern and attention left me humbled and amazed much of the time. I am deeply indebted.

May all beings benefit from my endeavors, and may we all attain Buddhahood quickly.

This article is available in Spanish: Transformando la Enfermedad en el Camino

Venerable Thubten Semkye

Ven. Semkye was the Abbey's first lay resident, coming to help Venerable Chodron with the gardens and land management in the spring of 2004. She became the Abbey's third nun in 2007 and received bhikshuni ordination in Taiwan in 2010. She met Venerable Chodron at the Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle in 1996. She took refuge in 1999. When the land was acquired for the Abbey in 2003, Ven. Semye coordinated volunteers for the initial move-in and early remodeling. A founder of Friends of Sravasti Abbey, she accepted the position of chairperson to provide the Four Requisites for the monastic community. Realizing that was a difficult task to do from 350 miles away, she moved to the Abbey in spring of 2004. Although she didn't originally see ordination in her future, after the 2006 Chenrezig retreat when she spent half of her meditation time reflecting on death and impermanence, Ven. Semkye realized that ordaining would be the wisest, most compassionate use of her life. View pictures of her ordination. Ven. Semkye draws on her extensive experience in landscaping and horticulture to manage the Abbey's forests and gardens. She oversees "Offering Volunteer Service Weekends" during which volunteers help with construction, gardening, and forest stewardship.