Prostrations to the 35 Buddhas

The Bodhisattva’s Confession of Ethical Downfalls, Page 1

Transcribed and lightly edited teaching given at Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle, Washington, in January 2000.

The text that we will study now is the Sutra of the Three Heaps (Skt: Triskandhadharmasutra). The three heaps or collections of activities that we do in conjunction with it are confessing (revealing our unskillful actions), rejoicing, and dedicating. This sutra is found within a larger sutra, The Stack of Jewels Sutra (Skt: Ratnakutasutra) in the chapter called “The Definitive Vinaya.” Nagarjuna wrote a commentary to this sutra entitled The Bodhisattva’s Confession of Ethical Downfalls (Skt: Bodhipattidesanavrtti), which is the name we often use in English to refer to the practice.

Why do we need to purify? Because our mind is full of rubbish. Have you noticed that your mind is full of all sorts of illogical thoughts, disturbing emotions, and obsessions? These afflictions are not the nature of the mind. They are like clouds covering the clear sky. They are temporary and can be removed. It is to our advantage to remove them. Why? We want to be happy and peaceful and to be free from suffering, and we want others to be so as well.

From our own experience, we know that under the influence of the afflictions—disturbing attitudes and negative emotions—we act in ways that harm ourselves and others. The results of these actions can go on a long time after the action itself has stopped. These two—afflictions and actions (karma)—are the true origins of our suffering, and we need to eliminate them. To do this, we must realize emptiness, the deeper mode of existence. To do this, we must develop concentration, and to do this, we first need to abandon destructive actions, engage in positive ones, and purify the destructive actions we have created in the past. The practice of prostrating to the 35 Buddhas and reciting and meditating on the meaning of The Bodhisattva’s Confession of Ethical Downfalls is a potent method to purify the karmic imprints that obscure our mind, prevent us from gaining Dharma realizations, and lead us to suffering.

Our mind is like a field. Before we can grow anything, such as realizations of the path, in it, we have to clean the field, fertilize it, and plant the seeds. Prior to planting the seeds of listening to Dharma teachings, we need to clear away the garbage in the field of the mind by doing purification practices. We fertilize our mind by doing practices which accumulate positive potential.

Purification practice is very helpful spiritually as well as psychologically. A lot of the psychological problems we have stem from negative actions we’ve done in this life and previous lives. So the more we do purification practice, the more we learn to be honest with ourselves. We stop denying our internal garbage, come to grips with what we’ve said and done, and make peace with our past. The more we’re able to do this, the happier and more psychologically well-balanced we’ll be. This is a benefit that purification brings this life.

Purification is also helpful for us spiritually and benefits us in future lives. It’s going to take us many lifetimes to become a buddha, so making sure we have good future lives in which we can continue to practice is essential. Purification eliminates negative karmic seeds that could throw us into an unfortunate rebirth in the future. In addition, by eliminating karmic seeds, purification also removes the obscuring effect they have on our mind. Thus we will be able to understand the teachings better when we study, reflect, and meditate on them. So to progress spiritually, we need to purify.

Despite all these benefits to be derived from revealing and purifying our mistakes, one part of our mind has some resistance to it. There’s the thought, “I’m ashamed of the things that I’ve done. I’m afraid that people will know what’s going on in my mind and then they won’t accept me.” With this in the back of our mind, we cover up what we’ve done and what we’ve thought to the point where we can’t even be honest with ourselves, let alone with the people we care about. This makes for a painful mind/heart.

The word “shak pa” in Tibetan is often translated as “confession,” but it actually means to reveal or to split open. It refers to splitting open and revealing the things we’re ashamed of and have hidden from ourselves and others. Instead of our garbage in a container festering under the ground, growing mold and gook, we break it open and clean it out. When we do, all the festering mess clears up because we stop justifying, rationalizing, suppressing, and repressing things. Instead, we just learn to be honest with ourselves and admit, “I made this mistake.” We are honest but we don’t exaggerate it either, saying, “Oh, I’m such an awful person. No wonder no one loves me.” We just acknowledge our mistake, repair it, and go on with our life.

The four opponent powers

The power of regret

Purification is done by means of the four opponent powers. The first one is the power of regret for having acted in a harmful way. Note: this is regret, not guilt. It’s important to differentiate these two. Regret has an element of wisdom; it notices our mistakes and regrets them. Guilt, on the other hand, makes a drama, “Oh, look what I’ve done! I’m so terrible. How could I have done this? I’m so awful.” Who is the star of the show when we feel guilty? Me! Guilt is rather self-centered, isn’t it? Regret, however, isn’t imbued with self-flagellation.

Deep regret is essential to purify our negativities. Without it, we have no motivation to purify. Thinking about the suffering effects our actions have on others and on ourselves stimulates regret. How do our destructive actions hurt us? They place negative karmic seeds on our own mindstream, and these will cause us to experience suffering in the future.

The power of reliance/repairing the relationship

The second opponent power is the power of reliance or the power of repairing the relationship. When we act negatively, generally the object is either holy beings or ordinary beings. The way to repair the relationship with holy beings is by taking refuge in the Three Jewels. The relationship with the holy beings was damaged by our negative action and the thought behind it. Now we repair that by generating faith and confidence in our spiritual mentors and the Three Jewels and taking refuge in them.

The way to repair the relationships we’ve damaged with ordinary beings is by generating bodhicitta and having the wish to become a fully enlightened buddha in order to benefit them in the most far-reaching way.

If it is possible to go to the people we have harmed and apologize to them, that’s good to do. But most important is to reconcile and repair the broken relationship in our own mind. Sometimes the other person may be dead, or we have lost touch with them, or they may not be ready to talk with us. In addition, we want to purify negative actions created in previous lifetimes and we have no idea where or who the other people are now. In other words, we can’t always go to them and apologize directly.

Therefore, what’s most important is to restore the relationship in our own mind. Here, we generate love, compassion, and the altruistic intention for those whom previously we held bad feelings about. It was those negative emotions that motivated our harmful actions, so by transforming the emotions that motivate us, our future actions will also be transformed.

The power of determination not to repeat the action

The third of the four opponent powers is the force of determining not to do it again. This is making a clear determination how we want to act in the future. It’s good to pick a specific and realistic length of time for making a strong determination not to repeat the action. Then we must be careful during that time not to do the same action. Through making such determinations, we begin to change in evident ways. We also gain confidence that we can, in fact, break old bad habits and act with more kindness towards others.

With regard to some negative actions, we can feel confident that we’ll never do them again because we’ve looked inside and said, “That’s too disgusting. Never again am I going to do that!” We can say that with confidence. With other things, like talking behind other people’s back or losing our temper and making hurtful comments, it may be more difficult for us to say confidently that we’ll never do again. We might make the promise and then five minutes later find ourselves doing it again simply because of habit or lack of awareness. In such a situation, it’s better to say, “For the next two days I won’t repeat that action.” Alternatively, we could say, “I will try very hard not to do that again,” or “I will be very attentive regarding my behavior in that area.”

The power of remedial action

The fourth opponent power is the power of remedial action. Here we actively do something. In the context of this practice, we recite the names of the 35 Buddhas and prostrate to them. Other purification practices include such activities as reciting the Vajrasattva mantra, making tsa-tsas (little buddha figures), reciting sutras, meditating on emptiness, helping to publish Dharma books, making offerings to our teacher, a monastery, Dharma center, or temple, or the Three Jewels. Remedial actions also include doing community service work such as offering service in hospice, prison, volunteer programs that help children learn to read, food banks, homeless shelters, old-age facilities—any action that benefits others. There are many types of remedial actions that we can do.

Initial visualization

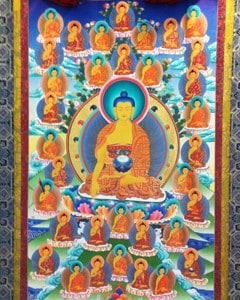

There are several different ways to visualize the 35 Buddhas. Je Rinpoche visualized all the Buddhas in a circular pattern around Shakyamuni Buddha. They were different colors with different hand gestures and hold different hand implements. There are some photographs and thangkas showing this way of visualization.

The visualization that I’m going to describe here is easier. Here, there are five rows of Buddhas, corresponding to the five Dhyani Buddhas. In general, all the Buddhas in one row have the same hand gestures and the color of a particular Dhyani Buddha.

Shakyamuni Buddha is above and in the center. From his heart, 34 light beams come out forming five rows. The top row has six light beams with six thrones, one at the end of each beam. Then, the second through the fifth rows all have seven light beams with seven thrones, one at the end of each light beam. Each throne is supported by elephants, indicating very strong purification because elephants are mighty. All the Buddhas sit on a seat of lotus, moon, and sun, symbolizing the three principal aspects of the path.

Shakyamuni Buddha in the center is golden in color and his hands are in the gestures generally depicted in paintings. His left palm is in his lap holding an alms bowl, and his right palm on his right knee with the palm down in the earth touching gesture. The text begins with,

To the Founder, the Transcendent Destroyer, the One Thus Gone, the Foe Destroyer, the Fully Enlightened One, the Glorious Conqueror from the Shakyas, I bow down.

That is the prostration to Shakyamuni Buddha.

In the first row with the six light beams are the next six Buddhas mentioned in the text. They resemble Akshobya Buddha and are blue in color. The left hand is in the lap in meditative equipoise, and the right hand is in the earth touching position with the right palm facing down on the knee. The fourth one, the One Thus Gone, the King with Power over the Nagas, is an exception. He has a blue body and a white face and his hands are together at his heart.

In the second row, the next seven Buddhas also sit on light beams and thrones. Prostrations to these Buddhas begin with

To the One Thus Gone, the Jewel Moonlight, I bow down.

These seven Buddhas resemble Vairocana. They’re white in color with both hands at the heart, the index fingers extended.

In the third row, prostrations to the next seven Buddhas start with

To the One Thus Gone, the Celestial Waters, I bow down.

These Buddhas resemble Ratnasambhava, who is yellow in color. His left hand is in meditative equipoise and his right hand rests on the right knee, palm facing outwards in the gesture of giving.

In the fourth row, starting with

The One Thus Gone, the Son of the Desireless One,

those seven Buddhas resemble Amitabha. They’re red and both hands are in their laps in meditative equipoise.

In the fifth row are seven green Buddhas starting with

The One Thus Gone, The King Holding the Banner of Victory Over the Senses.

They resemble Amoghasiddhi and are green. The left hand is in meditative equipoise and the right hand is bent at the elbow with the palm facing outward. This mudra is called the gesture of giving protection; sometimes it is also called the gesture of giving refuge.

Do the visualization as best as you can. Don’t expect to have it all perfect. The most important thing is to feel like you’re in the presence of these holy beings. As you say each name, concentrate on that particular Buddha.

Prostrating

Prostrations may be physical, verbal, and mental. We have to do all of them. Physically, we do short or long prostrations. When we do the purification practice with the 35 Buddhas, it’s nice to do the long ones. If you have physical limitation and can’t bow down, just putting your palms together in front of your heart is considered physical prostration.

Physical prostrations include the long and the short versions. Both begin with putting our hands together. The right hand represents method or the compassion aspect of the path, and the left hand represents the wisdom aspect of the path. By putting our two hands together, we show that we’re trying to accumulate and then unify method and wisdom to attain the form body and the truth body—the rupakaya and dharmakaya of a Buddha. Tucking our thumbs inside the palms is like coming to the Buddha holding a jewel—the jewel of our Buddha nature. The space in between our palms is empty, representing the emptiness of inherent existence.

Prostrations begin with touching our hands to our crown, forehead, throat and heart. First touch the crown of your head. On Buddha statues, the Buddha has a small protuberance on his crown. It’s one of the 32 major marks of an enlightened being. He received this due to his great accumulation of positive potential while he was on the bodhisattva path. The reason that we touch our crown is so that we, too, may accumulate that much positive potential and become a Buddha.

Touching our forehead with our palms represents purifying physical negativities such as killing, stealing, and unwise sexual behavior. It also represents receiving the inspiration of the Buddha’s physical faculties. Here, we especially think of the physical qualities of a Buddha. We imagine white light coming from the Buddha’s forehead into ours and think that the light performs those two functions: purifying the negativities we created with our body and inspiring us with the Buddha’s physical capabilities. We can also feel inspired by the nirmanakaya, the emanation body of a Buddha.

Next, we touch our throat and imagine red light coming from the Buddha’s throat into ours. This purifies verbal negativities such as lying, divisive speech, harsh words, and idle talk or gossip. It also inspires us so that we can gain the Buddha’s verbal capacities. These include the 60 qualities of an enlightened being’s speech. We can also think of the qualities of the sambhogakaya, the enjoyment body of a Buddha.

Then, we imagine deep blue light coming from the Buddha’s heart into ours. This purifies all mental negativities such as covetousness, maliciousness, and wrong views. It also inspires us with the qualities of the Buddha’s mind, such as the eighteen unique qualities of an enlightened being, the 10 powers, the 4 fearlessnesses, and so on.

To do a short prostration, now put your hands on the floor with your palms flat and fingers together. Then put your knees down. Touch your forehead to the floor and push yourself up. This is also called the five-point prostration because we touch five points of the body to the floor: two knees, two hands, and the forehead. That’s how to do the short prostration.

If you’re doing long prostrations, after touching your crown, forehead, throat, and heart with your hands, put your hands down on the floor, then your knees. Then put your hands some distance in front of you, lie down flat, and stretch your hands out in front of you. Next, put your palms together and lift your hands at the elbow as a gesture of respect. Some people lift their hands at the wrist. Put your hands back down, and then move them so that they’re about even with the shoulders, and push yourself back up to a kneeling position. Then, move your hands back again next to the knees, and at that point, push yourself back up to a standing position.

When doing long prostrations, some people slide the rest of the way down after putting their hands on the floor. That’s also ok. Just be sure to have some kind of pads under your hands, otherwise they get scratched up. When you move your hands on the way up, move both of your hands in sync, not one by one as if crawling.

Don’t stay on the ground long. In the Tibetan style of prostrations, we come up quickly symbolizing that we want to come out of cyclic existence quickly. In other traditions, such as the Chinese Buddhist tradition, they stay down for a long time to give more time to visualize. In this case, there’s a different symbolic significance in the prostrations, which has its own beauty.

Verbal prostration is saying the names of the Buddhas with respect.

Mental prostration is having deep respect, faith, and confidence in the Three Jewels and their ability to guide us. Mental prostration also includes doing the visualization with the lights coming to purify and inspire us.

Doing the Practice

It’s good to do this practice at the end of each day. Start by reflecting on the things in your day that you want to purify. Or, think of everything you’ve done since beginningless time and purify the whole batch. What’s best is to do the four opponent powers with respect to all negative actions done in this and previous lives, even if we can’t specifically remember them. We think of the ten destructive actions in general, but also pay particular attention to purifying the ones we do remember, whether we created them that day or earlier in our life.

Then, do three prostrations saying,

Om namo manjushriye namo sushriye namo uttama shriye soha.

Saying this mantra increases the power of each prostration so that it increases the purification and the creation of positive potential. Then say,

I, (say your name), throughout all times, take refuge in the Gurus; take refuge in the Buddhas; take refuge in the Dharma; take refuge in the Sangha.

Of the four opponent powers, that is the branch of taking refuge.

This is a good practice to do daily, in the morning to wake you up (among other benefits) and in the evening to purify any destructive actions you may have done during the day. Making prostrations is also one of the ngondro or preliminary practices. “Preliminary” doesn’t mean they are simple! It means we do them as preparation to Vajrayana practice, especially to purify and eliminate obstacles prior to doing a long retreat on a deity. Other preliminaries are taking refuge, offering the mandala, reciting Vajrasattva mantra, and guru yoga. In addition, more preliminaries are the Dorje Khadro (Vajra Daka) practice, the Damtsig Dorje (Samaya Vajra) practice, offering water bowls, making tsa-tsas. As a preliminary practice, you do 100,000 of each of these, plus 10% to make up for any errors, for a total of 111,111.

If you do prostrations every day and are not counting them as part of your ngondro, you can repeat one name of a Buddha after the other while prostrating. Then continue to prostrate while saying the prayer of the three heaps—confession, rejoicing, and dedication.

If you’re counting the prostrations, an easy way to count it is to do one prostration to each Buddha while reciting that Buddha’s name repeatedly. Some names are shorter so you can say more of them during one prostration; others are longer and you can’t say as many. It doesn’t matter. By bowing one time to each Buddha, you know that you’ve done 35 prostrations right there so you don’t need to be distracted by trying to count them. Count the number of prostrations you do while reciting the prayer of the three heaps. If you do this a few times, you will know approximately how many you do during each recitation. Thereafter, instead of counting each time you do the prayer, just add in that approximate number. In that way counting doesn’t become a distraction. This is important, for you should focus on having regret, doing the visualization, and feeling purified, not on counting numbers.

To memorize the Buddhas’ names, make a tape and say the name over and over again as many times as it takes to do one prostration. The more times you say the Buddha’s name, the more positive potential you create. Another way is to keep the book next to you, read one name and then say it over and over as you do one prostration. Then, when you’ve done that one, read the next Buddha’s name and say it over and over as you do the second prostration. As you say each name, think that you are calling out to that Buddha with the intention, “I want to purify all this rubbish so I can benefit sentient beings in the best way.”

Memorizing the names is very helpful because then you can concentrate on the visualization and on feeling regret, admiration and respect for the Buddhas’ qualities, trust and confidence in the Three Jewels. The sooner you can memorize the prayer, the better the practice will be for you because you won’t be distracted by, “Which Buddha? What’s his name? I can’t remember.”

Another way to do the practice in which counting is easy is to recite the names all the way through one time, while prostrating to each one, and do that several more times and say the prayer of the three heaps once at the end. That is, you can do several sets of names and then the prayer. It depends how you like to do it. It’s up to you.

While you’re prostrating, think about specific things you want to purify. That will help you be more aware and conscious in your life and to reflect upon what you’ve done. It’s also good to think you’re purifying all the actions in a broad, general category, because who knows what we’ve done in our previous lives? So don’t just dwell on the fact that you criticized your sister today and forget to regret and purify all the other millions of times we’ve criticized others throughout infinite beginningless lives. We want to purify the whole lot of negative karma, although we might focus on certain actions that are really weighing heavy on us and think of them specifically when we do it.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.