The most stable people in prison

By R. L.

R. L. has spent thirty years in prison for a crime committed at age 19. During his correspondence with Venerable Chodron, he once said that the men who were in prison for murder tended to be some of the most likeable people. Surprised, she asked him to explain. This is his response.

As things go, yes indeed, people who have committed murder usually do represent the most stable and likeable segment of the prison population. I realize how unlikely that sounds, but it is usually true. With the exception of those who obviously enjoyed what they did—and the number of them is remarkably small—most incarcerated people serving prison sentences for murder are first-time offenders that committed a “crime of passion,” and are extremely unlikely to repeat—any offense—if released. Within the prison population, they are generally the quietest, most stable, and peaceful. They are not usually the source of problems common to most prison environments.

I suppose, by virtue of the nature of their offense, they are usually considered “dangerous,” “threatening,” and a host of other adjectives. Actually, the opposite is often the case. And it is these long-term offenders serving sentences for murder that usually participate in virtually every beneficial and productive program available. Of course, as with virtually anyone or anything, there are exceptions. This is as true with those convicted of murder in prison as with anything else. There are those that relish what they have done, for whatever reason, and plan to continue those kinds of activities if ever released. Personally, I believe it has something to do with a mental disorder, but whatever the cause, most of us are aware of those that enjoy inflicting pain and misery on others, and the vast majority of people avoid them. They are a kind of sick breed unto themselves. They are like the cruel little children that pull the wings off beautiful butterflies and skip off laughing and giggling at their atrocity. These people represent a very small minority within the prison population.

Most of those convicted of murder also spend such lengthy periods of time within a prison setting that they become known to everyone. We usually become known for our stability and our peaceful demeanor. When those of us that have served a long time behind concrete and steel do get released, we are virtually guaranteed to succeed—basically, we have had more than our fill of prison.

Other individuals, however, do not fare so well, either inside or outside of prison. Those convicted of lesser crimes tend to be untrustworthy; they steal from other incarcerated people and staff if possible; they cheat and lie, etc. That kind of behavior inside prison usually creates tensions and other problems. That sort of behavior is continued after release as well, and they usually become recidivists.

Prison, obviously, is a very strange place, with all its own rules of conduct, appropriate behavior, etc., and is often difficult to describe to someone that hasn’t shared the horrible experience. It’s far stranger than most people can even begin to imagine. Every extreme is represented, and those extremes are taken to the extreme. There is a kind of intensity extant in prison like no place else in the world; every moment is like one’s last, and causes behavior that can only be described as hopeless-to-dangerous. There are stories I could relate to you … then again, probably not, let’s simply say that if I had to be locked in a dark room with a bunch of incarcerated people, I’d prefer it to be a bunch of killers rather than thieves and rapists!

Venerable Thubten Chodron: I found what R.L. wrote interesting.

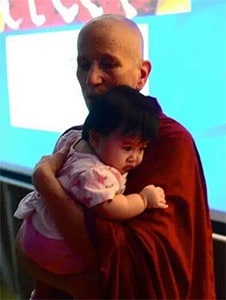

With two Zen priests and members of Mahabodhi Society before entering San Quentin (April, 2005).

It made me remember an event several months ago when I gave a Dharma talk to the Buddhist group at San Quentin Prison in California. Afterwards, I spoke with the group, one of the men who told me that most of the guys in Buddhist group were lifers, usually for murder. He said that because they knew they’d spend their life in prison, they weren’t waiting for something else better or more exciting to happen and thus were making the best life they could for themselves in prison. For many this meant spiritual practice, because that was what brought meaning to their lives. It also helped them work with the difficult conditions they encountered in prison. He said the guys who were in for a shorter time, due to less severe crimes, were usually much angrier at being locked up. They constantly thought about the future, thinking what they would do when they got out and planning for future pleasure or future revenge. It would make sense that these people would cause more conflict with others while in prison.

Incarcerated people

Many incarcerated people from all over the United States correspond with Venerable Thubten Chodron and monastics from Sravasti Abbey. They offer great insights into how they are applying the Dharma and striving to be of benefit to themselves and others in even the most difficult of situations.