Prison of desire

By A. B.

A. B., a veteran of the Vietnam War, served 20 years in a maximum security prison in southern Indiana. He was released in April 2003. An ordained priest in the Pure Land Buddhist tradition, he is currently in residence at Udumbara Sangha Zen Center in Evanston, Illinois. This article was reprinted with permission from Tricycle Magazine, Spring 2004

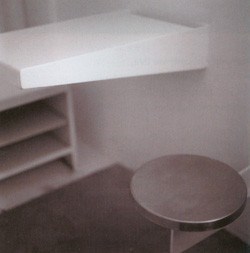

Every day of the 20 years I spent in prison for armed robbery, I heard the word freedom tossed about as if it were a prayer. For all of us convicts, it meant the same thing: to get out, to be back in the world. This wonderful notion of freedom—it occupied our days, our dreams, our fantasies. And for all that talk of freedom, few of us could see that we were in bondage long before we ever went to prison. Years of my life were spent in a prison of my own desires and aversions: I used drugs, alcohol, and relationships like they were aspirin.

I resisted meditation practice my first few years inside for the simple reason that I couldn’t be alone with myself. The pain of seeing what was in my heart was too great. I could navigate the world of prison much more easily than I could the cesspool of my own mind. The thoughts I had were of mayhem, violence, sex, drug relapses. In my mind I had murdered, raped, stolen, and maimed. I did not want to be alone with that person.

When years had passed and I finally summoned the courage to turn and face myself, I thought I could manipulate my mind. I would sit for hours and try to direct my thoughts away from the anguished memories of the past, the recriminations, the bitterness, and the violence. It didn’t dawn on me that I had no control over the arising of my thoughts. I was not thinking the thoughts; they were thinking themselves. When I realized this, I was profoundly relieved. The thoughts were not me, and whatever judgment I might make about them was totally unnecessary. My responsibility was only to sit with them, without motive, agenda, or intention.

When I look for freedom today I find it not in fantasy or in dreams, but in my sitting practice. What kind of freedom is it that exists in doing nothing? It is the freedom not to interfere or react. It is the freedom to merely observe. I don’t have to judge the trauma that arises in my mind. I don’t have to get involved with the hundred narratives that might try to occupy my mind during the day. In not clinging to thoughts and ideas, wants and desires, hatreds and resentments, the bondages of my most negative thoughts and emotions have faded into a haze that still arises but no longer dominates my life. I have found freedom: it is the freedom of nonattachment, the freedom to not cling and to not resist. It is the freedom to allow myself to be with myself.

Incarcerated people

Many incarcerated people from all over the United States correspond with Venerable Thubten Chodron and monastics from Sravasti Abbey. They offer great insights into how they are applying the Dharma and striving to be of benefit to themselves and others in even the most difficult of situations.